By Raeanne Raccagno

Copy Editor

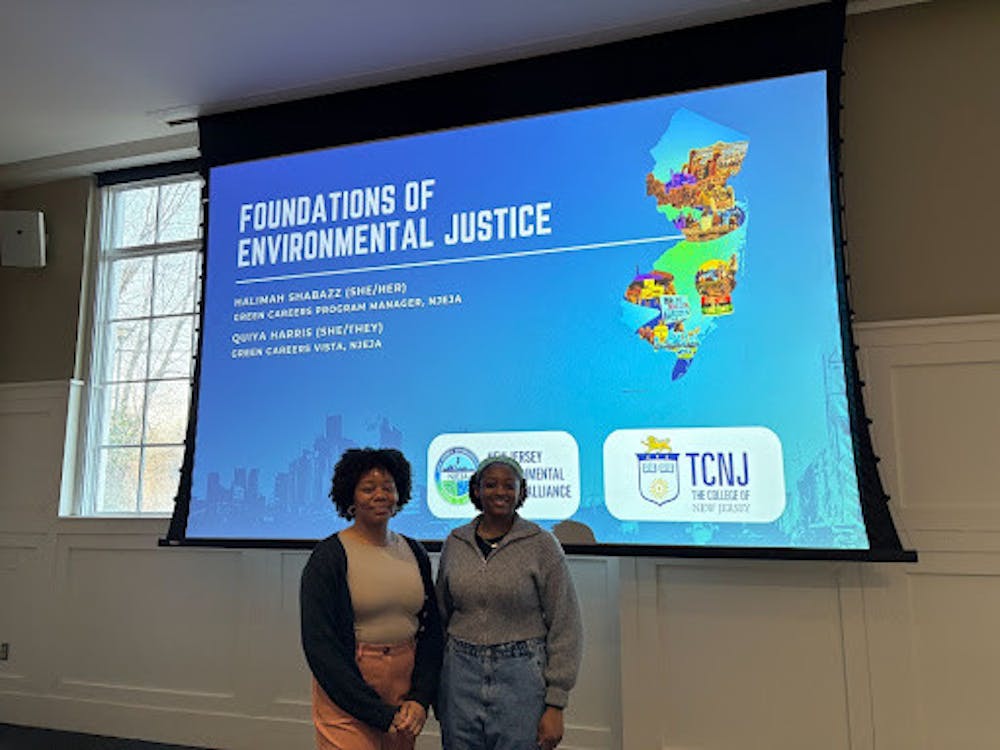

Two representatives from the New Jersey Environmental Justice Alliance gave a presentation on March 12 at the College about environmental injustice and how affected communities and others are fighting against it.

Halimah Shabazz, Green Careers program manager for NJEJA, and Quiya Harris, Green Careers vista for NJEJA, shared their experiences of living in areas that were not as environmentally friendly compared to surrounding residences.

“Although I lived across the street from a park, there were so many things around me that let me know that my neighborhood was not as cared for as the surrounding neighborhoods,” Shabazz said. “Due to things like lots of trash and the sewers and catch basins, there weren't really a lot of trees.”

According to their website, NJEJA is a coalition of New Jersey-based individuals and organizations who are united to “identify, prevent, and reduce and/or eliminate environmental injustices that exist in communities of color and low-income communities.” Some of their efforts include supporting impacted neighborhoods’ efforts to rebuild and remediate.

The primary focus of the presentation discussed the struggles current overburdened communities are facing and some of the efforts underway to help release them. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency describes overburdened communities as low-income, minority, tribal and Indigenous populations with a greater exposure to environmental hazards, potentially experiencing disproportionate environmental risks.

Shabazz described New Jersey’s Environmental Justice Law as a “huge win.” It requires the Department of Environmental Protection to assess possible impacts some firms could bring to overburdened communities’ environmental and public health.

The development of overburdened communities is a result of redlining. Redlining is the practice of withholding services, especially mortgages, to those who live in neighborhoods declared as “hazardous.”

Harris said the term “hazardous” came from the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation, which ceased in 1951. In 1968, redlining was outlawed with the Fair Housing Act, and Shabazz said environmental justice was essentially born in 1970.

The start of environmental justice came from a middle-class Black neighborhood in Houston, raising questions about a solid waste facility in their area. According to Shabazz, 80% of the waste tonnage that was in Houston was in Black neighborhoods, and at the time, only 25% of the city’s population was Black.

Harris quoted a news article by NJ Spotlight News that said Camden was a redlining hotspot in the U.S.

“This just underscores that the practice still exists, even if it goes by a different name or no name at all, or if people are still taking elements of the original practice of redlining and applying it today,” Harris said.

She also explained the multitude of social, economic and environmental challenges that formerly redlined neighborhoods face, including health issues like increased risk of cardiovascular disease, cancer, asthma and diabetes, reduced life expectancy and increased reproductive risks, especially during pregnancies.

Redlining is also the biggest contributor to sacrifice zones, which are populated areas with high pollution levels and environmental dangers. The pollution comes from nearby toxic industrial facilities or brownfields, which are former commercial sites that are unusable from pollution.

Discussing the surrounding area, Harris said that one of Trenton’s biggest environmental injustice issues is brownfields due to its industrial history. She said that the decontamination process is very difficult and takes years to complete.

Trenton also suffers from lead in soil and water, illegal dumping, hazardous oil and waste runoff from businesses, sewage overflow, lack of access to healthy foods and green spaces, flooding and air pollution.

“I do want to note that a lot of these issues and their impacts are felt outside of the city confines of Trenton, especially air pollution, because the air is not going to stop at a city border,” Harris said.

The pair also showed a trailer for a documentary, “Sacrifice Zone,” which highlights the Ironbound neighborhood in Newark, one of the neighborhoods in New Jersey with the most polluting facilities.

The two also shared their involvement with recent Newark community efforts against the Passaic Valley Sewerage Commission starting a fourth gas-fueled power plant in the city.

The approval to begin the power plant was given by New Jersey’s DEP in February. Mayor Ras J. Baraka of Newark stated in the same month, “In a city struggling to dig out from under decades of environmental injustices, the state’s greenlighting of Passaic Valley Sewerage Commission’s construction of Newark’s fourth gas-fueled power plant comes as an assault that we are prepared to fight in court.”

The Ironbound Community Corporation, founded in 1969, along with other environmental leaders, has been speaking out against the construction, and recently the company has decided to table the decision.

Along with local efforts to combat environmental injustice, Shabazz and Harris also encouraged students to take advantage of their school’s resources to learn more about the issue and to help navigate interest in a green career.

“All work towards it [environmental injustice] is useful,” Shabazz said. “That goes by engaging with those people in the community, engaging with people in your community, not just doing something that you think is helpful, but asking, 'hey, what is actually helpful here?’ That's how you make it more meaningful and so it doesn't feel like it's for nothing.”

Another focus of the talk was the mental health attacks that residents in environmentally underserved areas experience and how to incorporate emotional support in environmental justice actions.

“These different types of air pollution can cause a lot of different types of mental health effects,” Harris said. “The biggest one being chronic stress in high levels of cortisol, because that can absolutely ruin your body in so many different ways. A lot of them also cause anxiety and depression.”

She also explained how a mixture of pollutants in the air can have unpredictable effects on medication, since residents will not know what type of exact contaminants they’re breathing in, and how contaminated air can cause cognitive decline, particularly in older generations. Contaminated water in districts can also lead to cognitive impairment and developmental issues in children.

“What messages are you sending to children that grow up in these communities?” Kathleen Grant, associate professor of counselor education and organizer of the event, said during the forum. “And just putting on a mental health lens, how that can impact children's feelings of worthiness in the long run.”