By Rajika Chauhan

Staff Writer

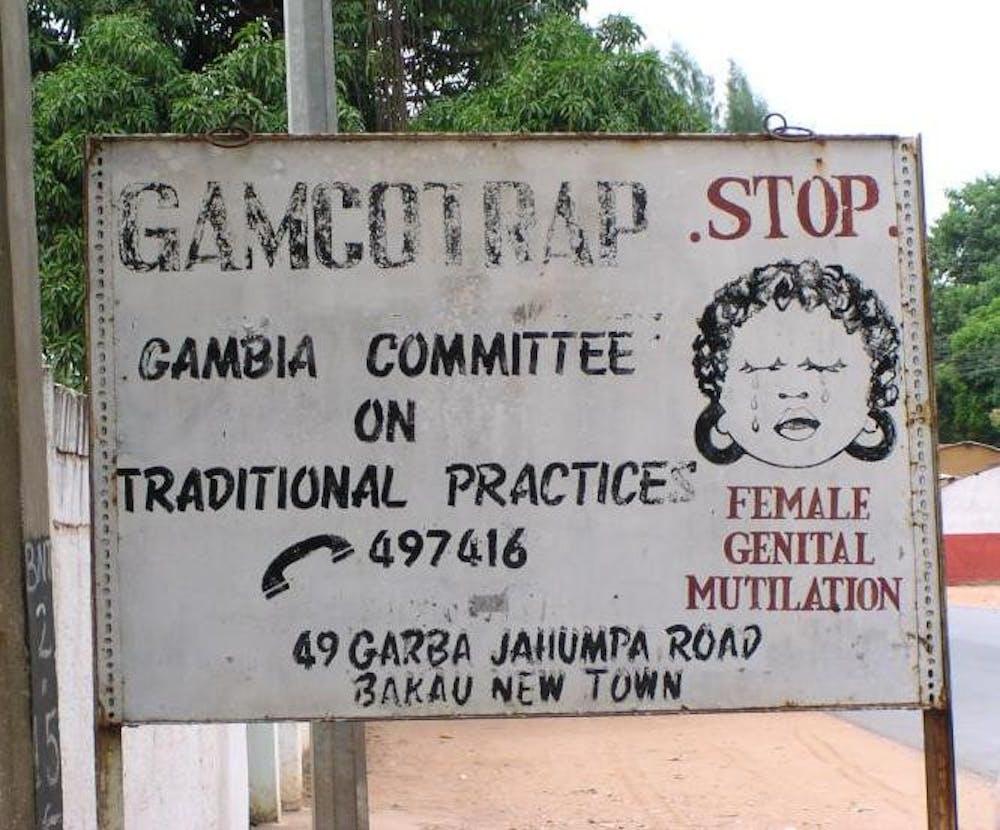

In a landmark decision, Gambian lawmakers ruled on March 18 to advance a measure seeking to overturn the nationwide ban against the practice of female genital cutting. The current law prohibiting the practice across the nation has been in place since 2015. Despite this, the law has been weakly enforced since its inception, generating little recourse other than three fines handed to practitioners last year.

A majority of members, 42 out of 47, in the Gambia National Assembly, voted to pass a bill repealing the ban forward to a committee, where it will be subject to a final vote, according to the New York Times.

Female genital mutilation refers to all procedures involving the partial or total removal of external female genitalia, and is typically performed shortly after birth, although it can occur later into adolescence. There are no recorded health benefits to FGM, as it is commonly abbreviated, and is associated with severe health risks, according to UNICEF.

Cutting is typically performed by traditional circumcisers who have no medical training. The lack of hygiene and proper medical procedure can lead to infection, transmission of HIV, severe and lifelong pain, hemorrhage and shock. Girls with FGM have been recorded to experience later complications during childbirth, including stillbirth or postpartum hemorrhaging. At least 230 million girls from 31 countries have been recorded to have undergone FGM, although exact estimates are difficult to provide. Africa accounts for 140 million of this total, according to the United Nations Population Fund.

Genital cutting is a ritual deeply embedded in certain global cultures, according to UNICEF. The rationale behind FGM lies in notions of preserving female purity and suppressing female sexuality, which certain cultures believe to be destructive. It is believed to ensure that a woman will remain a virgin before marriage, and is often seen as a girl’s transition into womanhood. Social pressures continue to enforce the practice over generations, including the perception of cutting as a requirement for marriage, to prevent social ostracization and religious doctrine.

In Gambia, more than 75% of women report having undergone cutting, as stated in the NYT. A ban against the practice was first instituted in 2015, under President Yahya Jammeh, amidst widespread international criticism and pressure from humanitarian organizations who have deemed the procedure a violation of human rights. Jammeh called those who fought to end FGM “enemies of Islam.”

Clerics in Gambia have argued over whether cutting is an Islamic practice as it is not mentioned in the Quran. One outspoken imam, Abdoulie Fatty, has claimed, however, that circumcision “makes you cleaner” and that women who have not been cut have “insatiable sexual appetites.”

At the bill’s first reading, Fatty organized a group of young women with their faces veiled to chant slogans outside Parliament, waving posters and singing “female circumcision is our religious beliefs.”

Since the ban, a strong opposition has risen up in favor of FGM, led by Fatty, who has claimed that the practice is a religious obligation, according to the NYT.

Many advocates of the ban expressed frustration over the bill’s life being put in the hands of majority-male lawmakers. Only 5 of the 58 lawmakers in Gambia are women. Arguments issued in the Parliament ranged from those in favor of maintaining the ban to those that invoked religious and traditional justifications, according to the NYT.

“If people are being arrested for practicing F.G.M., then that means they are being deprived of their right to practice religion,” said Lamin Ceesay, a member of Parliament.

Critics also say that the ban will undo the progress that has been made in reducing the societal stigma against cutting. Some argue that politicians who do not personally believe in the practice are continuing to stand behind it out of their own political interests, according to NYT.

The vote to determine whether the ban will hold is to be decided in several weeks. If reversed, it will mark an unfortunate turn in the fight to overcome what has been a ritual entrenched in centuries of tradition and societal pressures. However, opponents of cutting have voiced a strong refusal to back down, continuing forward with the resolve that FGM can be eliminated in one generation.

Fatou Baldeh, a leading opponent of FGM in Gambia said, “If you don’t cut a girl, she’s not going to cut her future daughters.”