By Joshua Hudes

Correspondent

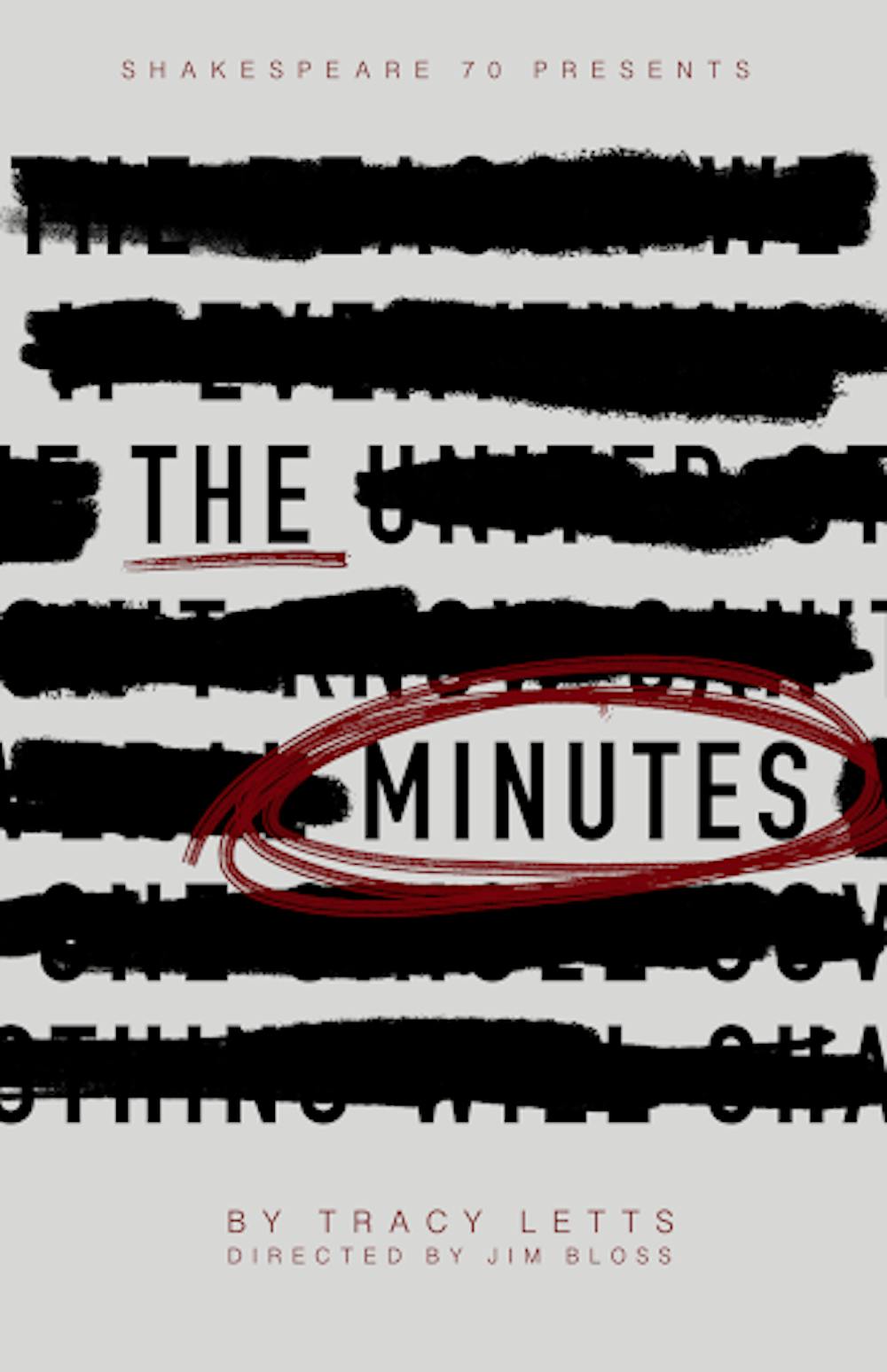

A play which succeeds in provoking an audience the way “The Minutes” did could only have been written by the great American playwright Tracy Letts. Having started its run here at the College on March 20 and closing shop on March 24, audiences for five evenings straight were given an exuberant and well-mannered display of confined and claustrophobic acting tour-de-forces.

The theater company responsible for such a production is none other than Shakespeare 70, which produces plays from across all time periods beyond Shakespeare himself. One particularly esteemed member of this company is the director of this production, Jim Bloss. Bloss has been an active member of Shakespeare 70 since 2013 with a number of roles, and made his directorial debut with this show.

As previously espoused, the maximalist performances from this brilliant set of actors seemed to have been carefully attuned by Bloss to highlight the emotional highs and lows these characters go through. Poignancy is quite the understatement in regards to a story about a fictional town named Cherry Hill whose typical city council meeting is upended by historical revelations, the likes of which have never been reckoned with before.

The town appears to have been built upon the blood of those who had fallen during one of many hostile conflicts between settlers and Native-Americans within that time period. The 1876 Great Sioux War between the Midwestern native Lakota and Cheyenne tribes and the U.S. military comes to mind as inspiration. It was a conflict which got its foot off the ground with the violation of pre-established land treaties and came to its tragic conclusion with the use of sheer brute force at the hands of the U.S. in placing the natives into carefully allotted reservations.

Letts’ story wants most of these truths to be made apparent to the viewer by the story’s end, yet at the same time has framed a story of self-deception around it. There are simply too many characters in this “12 Angry Men”-inspired work to keep track of in a single review. Yet it is important to make note of a certain character who has unearthed a hidden truth about who really provoked the conflict within these Native-American lands. As a result, this character quite unsubtly becomes silenced on the grounds of providing their offspring with “optimism.”

Letts is a writer who earlier dabbled in Postmodern works — most notable of all being his Tony Award-winning play, “August: Osage County.” In that play, regret and familial guilt rested out in the open inconspicuously atop a firm table whose legs were weakened until the entire foundation collapsed. In a similar vein, “The Minutes” leverages much of its staying power on account of the fact that there’s always the foreboding feeling that something either literally or figuratively is about to collapse.

The context of what this routine meeting exactly entails is not revealed immediately to the audience, but is rather expressed through lengthy back-and-forth monologues and rapid exchanges between characters. Several interpretations concerning how this play could be expressing with its words the collapse of language itself came to mind. Two notable characters quarrel on the true difference between semantics and linguistics, one being the study of meaning in language and the other being the study of structure in language.

A series of both trite and prickly comments are either disputed or left to be chuckled off at by the viewer for its complete lack of conviction or purpose. One of the issues brought up at the meeting concerns a new event at the town’s upcoming festival called the Lincoln Brawl, whereby anyone can have the chance to have a violent tussle with the former president. This recalled those freak shows in which violence and power were brought to the surface for a cathartic release. Within this specific instance, acts of machismo are thrusted upon a leader whose words and proclamations would continually be reinterpreted to favor the “winner” of history.

Beyond the figurative, the constant power outages of the building in which they are residing in, coupled with the rainstorm regularly brewing on the periphery, make it seem as if a literal collapse of the stage itself is a potentiality. Bloss indescribably discovers so many minute avenues within the construction of the set design with which to have every part of the set feel useful and lived in. It truly makes the audience feel the ordinariness of such proceedings.

The words of Letts and the direction of Bloss might seem to want the viewer to feel uncomfortable in that regard. Without giving it away, the ending goes past any form of rational narrative conclusion and instead becomes a bestial display of synergistic, blood-totting rage more in line with experimental or avant-garde theater.

Whether it simply represents a cult mentality, the appropriation of past blood or even the exorcizing of the audience’s anger, it does paint an unnerving portrait of the nation. It is an ending which is figuratively at a loss for words just like those in the show are, playing nicely into the theme of language.

“History is a verb” is the line which shook me the most, not just because it is really a noun but because the implication surrounding who stated it calls to mind how most of history was at points written by the winners. It also reminded me of how, coming straight from the title, this play is not just about meeting minutes but also about the concept of time.

Within the pantheon of theatrical plays written and performed for a mass audience, rarely has one of such distinctions made its minutes go by so rapidly. Yet for how fast those 90 minutes fly by, an unsettling notion regarding time slipping away may begin to simmer towards the surface for the viewer.

The lost time which I refer to concerns a certain conflux of historical consolidation amongst the American population which might never find its just impartiality. Time, on the other hand, has chugged forward for however long humans have existed on this planet. With those additional minutes in mind, there could be a chance time might continue to remain on our side so that history might finally become a noun.