By Lilly Ward

Staff Writer

In the Princeton Bainbridge Gallery’s latest exhibit, “Reciting Women: Alia Bensliman & Khalilah Sabree,” two Muslim-American artists based in Trenton draw on their personal and spiritual experiences. The exhibition is an exploration of imagery in order to document and honor the constant evolution of cultural identity.

The work of Alia Bensliman, born Tunis, Tunisia, and Khalilah Sabree, born Macon, Georgia, offers insight into the challenge of bridging tradition and modernity as well as the sacred and the secular.

In Sabree’s work, the resilience of the human spirit in the face of war and oppression lingers between layers of transparent figures and architecture. Her suite of paintings, “Destruction of a Culture,” stemmed from a picture taken during hajj – the annual pilgrimage to Mecca. The image depicts two African women looking over a fence with their backs to the Kaaba, a shrine located near the center of the Great Mosque in Mecca.

Each of these works has about the same dimensions as a window, offering an intimate view into the loss and destruction of community life that results from war.

“Destruction of a Culture” contains images of a deteriorating crumbling city with figures who have a ghostly but strong presence on the canvas. Their existence orients the viewer in the scenes that unfold as women grasp prayer beads and look on towards the future they now face literally. The rough quality of the deteriorating architectural features is contrasted with the soft folds of fabric of the women’s garments. There are glimpses of hope amidst the turmoil: A string of prayer beads or a blue sky peeking out through an archway, depicting the surroundings as sacred. Despite the precariousness of their surroundings the women persist.

“When Things Fall Apart,” 2016-2017, Khalilah Sabree (Photo by Lilly Ward / Staff Writer)

“They are not mere onlookers but active participants, able to foresee a changing world that remains hidden from others,” said Sabree in her artist’s statement.

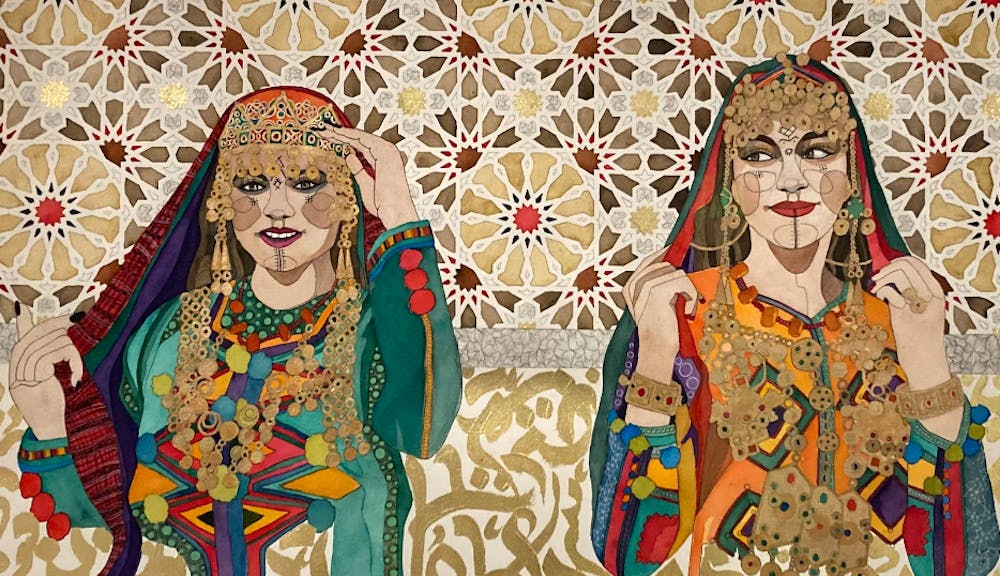

Bensliman’s paintings also represent women at a crossroads. Her work is inspired by her roots which belong to a diverse grouping of distinct ethnic groups indigenous to North Africa, known as the Amazigh. She incorporates in the background of her portraits patterns that reference a style of mosaic tilework made from individually hand-chiseled pieces known as zellij. This kind of tilework is unique to the architecture in Morocco, Algeria and Tunisia. Bensliman remembers seeing the mathematical, exact patterns of zellij tiles everywhere in the architecture of Tunisia. In her portraits of Amazigh women, Bensliman creates a contrast between the precise lines of the zellij patterns and the delicate sweeps of color used to portray the subject.

She portrays the identity of the women through their elaborate jewelry and tattoos. A woman with a tattoo of a moon and stars symbolizes her motherhood, while another represents a palm leaf, a symbol associated with marriage. The combination of the traditional garments, jewelry and patterns heighten the intensity of the figure’s presence. This potent combination allows the viewer to revel in the celebration of cultural identity and the traditions and legacies that the women embody.

The character lended to the portraits modernizes them. Each of the women are distinct individuals. In Bensliman's piece, “Symbiotic Juxtaposition,” the two women’s personalities are opposite but complementary.

“One is mischievous and one is reserved,” said Bensliman in her artist’s statement. “The arabesque and calligraphy are also distinct, yet they complement each other.”

There’s a sense of urgency in her work related to keeping this balance between individuality and collectivism, as best represented by her triple self-portrait which is about “always trying to find a balance.”

In “Me Myself and I : Unfinished Conversation,” there are three images of the artist on the canvas. Rendered in a vivid watercolor palette, this triple self-portrait mirrors the duality of the multiple roles taken on in Bensliman’s lifetime. She is a mother, an artist and an immigrant.

The portrait in the middle is surrounded by a golden halo of calligraphy, breaking the zellij pattern. The woman in the center stares directly back at the viewer, as if to assert her ability to embody and balance all three roles at once.

In both Sabree’s and Bensliman’s work, duality exists. There is the assertion of identity that exists while celebrating cultural belonging, and the ability to find the sacred even while surrounded by loss.