By Jane Bowden

Managing Editor

It was 8 in the morning when Madison Foglia tended to her patient, a healthy 40-year-old man who appeared to be suffering from a case of pneumonia.

Two hours later, the man was breathing 60 breaths per minute (the normal respiration rate for adults is 12 to 26 breaths per minute), needed 100 percent oxygen and was sent to the hospital’s intensive care unit to get intubated — he had COVID-19.

“Nothing I learned in four years of nursing school or seven months working as a (registered nurse) could have really prepared me for the overwhelming, unpredictable COVID-19 pandemic,” Foglia (’19) said.

As of May 4, there are 5,287 people hospitalized for COVID-19 in New Jersey, and as hospitals flood with patients, nursing students and alumni of the College work on the front lines of the pandemic.

Foglia started working as a nurse at Capital Health Medical Center in Hopewell Township, NJ in August 2019. Prior to the COVID-19 outbreak, she worked in the hospital’s telemetry unit, where she treated patients who had suffered from heart failure, strokes and other life-threatening conditions. Since Foglia’s floor was known for being fast paced and busy, she was used to working 12-hour shifts and taking only 10 minutes for a lunch break.

Today, Foglia’s day looks much different.

Wearing two masks, a tyvek suit, a hair cap, a face shield, gowns and gloves — all of which she often must rewear for multiple shifts due to a supply shortage — Foglia works three to four 15-hour shifts each week and tends to four to five COVID-19 patients each day.

With an influx of patients and limited staff, Foglia isn’t just her patients’ nurse — she must also take on the role of being their respiratory therapist, housekeeper, phlebotomist and nurse aid. It’s a job that places a heavy burden on any healthcare worker, but as a new nurse, Foglia finds the toll of the pandemic especially difficult, as she’s still “trying to develop (her) time management and prioritization skills.”

“The emotional, mental and physical stress I have experienced over the past weeks outweighs any stress I’ve experienced in my short career,” she said. “I feel compelled to take care of patients, no matter how infectious they are, as long as I am protected. But I no longer feel safe.”

Just 40 minutes away from Capital Health Medical Center is the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, where Kayla Mosser (’19) is watching the pandemic take a toll on her co-workers.

“I’ve seen nurses picking up more night shifts, so they can be with their kids during the day, running on zero sleep but managing to get by. I’ve seen exhausted doctors saying they are going home for the first time in three weeks and will probably spend their whole time home sleeping,” Mosser said. “Everyone is making sacrifices.”

For Mosser, the harsh reality of the pandemic doesn’t stop when she leaves the hospital.

Mosser lives in an apartment with her roommate, who also works as a nurse at CHOP. To protect themselves when they come home from the hospital, both Mosser and her roommate immediately take off their scrubs and place them in the wash, shower and self-isolate, only leaving the house when they need to.

Although Mosser isn’t living with her family, she still worries about them every day — her father works as an engineer at Holy Name Medical Center in Teaneck, NJ, where he “builds more (intensive care units) to accommodate the influx of COVID patients.”

“I worry about him, stretching himself so thin, and being exposed to COVID every day,” Mosser said. “He has been working and sleeping at the hospital the past three weeks, and there is no end in sight.”

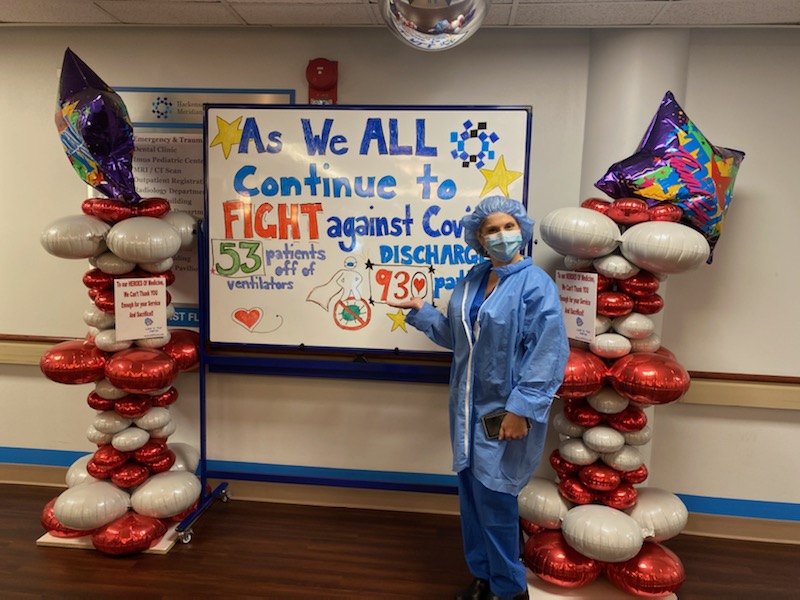

Nancy Flade (’85), a nurse at Hackensack University Medical Center, has seen her hospital change a lot in the past 29 years — but she’s never seen anything like this.

When COVID-19 patients first started to flood the hospital, Flade said it “felt like it was like doom every time you walked in, because things were changing so fast.” To accommodate the influx of patients, many rooms throughout the hospital were changed into COVID-19 units, such as the cafeteria, which now holds 75 beds.

Although Flade doesn’t work directly with coronavirus patients, she still feels the effects of the pandemic. As the death toll increases, morgues have become overcrowded, forcing hospitals to create temporary spaces to hold the dead.

“I did have to bring (one of my) patients who died (from an illness unrelated to COVID-19) to one of those refrigerator trucks,” Flade said. “It was horrible. A vision I will never forget.”

Carly Mastrogiacomo (’19), who is also a nurse at Hackensack University Medical Center, has been working on her hospital’s COVID-19 floor, where she tends six to eight patients who are in unstable condition each day. Due to overcrowding, she hasn’t seen many of her co-workers in weeks, since everyone spends hours in their own patients’ rooms.

To slow the spread of the novel coronavirus and keep people safe, many hospitals, including Hackensack University Medical Center, have adjusted its visitation policy, allowing only one to two visitors per patient or no visitors at all. Although Mastrogiacomo understands the need for the policy change, she said it’s still difficult to see her patients FaceTime their loved ones, as they try to make medical decisions over the phone.

“I can hear the anxiety in their voices, and sometimes I really am at a loss of what to say to make them feel better,” Mastrogiacomo said. “Sometimes I feel really helpless myself and wish I had answers for them, but we just haven’t completely figured this thing out yet.”

While hospitals become overwhelmed with COVID-19 patients, many nursing students from the College have been working alongside healthcare workers across the state.

Kerri McSweeney, a senior nursing major, joined Newton Medical Center in Sussex as a nursing assistant in June 2019, where she worked once a week on various floors of the hospital and tended to eight to 12 patients a day.

Prior to the pandemic, McSweeney said that before entering a patient’s room, she would wash her hands, wear gloves and a surgical mask, and could look at her patient with a full face. Every time she entered another patient’s room, she would put on a new mask and gloves.

But since March 20, McSweeney has been working almost every day on the hospital’s three units that are designated to treat COVID-19 patients. Now when she enters a patient’s room, she’s dressed head to toe in layers of personal protective equipment, all of which she wears for her entire shift. To further protect healthcare workers, the patients must also wear a mask.

“My legs are sore, my face and ears are sore from the masks, my hands are dry from washing so much, but none of that amounts to the pain and suffering these patients could be in,” McSweeney said.

But even as the virus continues to spread, there are signs of hope.

On April 30, the number of hospitalizations related to COVID-19 in New Jersey fell below 6,000, which is the first time that has happened since state officials started to track the data in early April, according to NJ.com.

Although the state has not yet released the number of New Jersey residents who have recovered from coronavirus, hundreds of patients have been discharged from hospitals each day, including Foglia’s 40-year-old patient, who, after 28 days in critical condition, made a full recovery.

“While the challenges of battling this virus seem endless, my determination has grown even stronger. I feel a greater sense of purpose knowing I have a lot of people relying on me,” Foglia said. “Although I am not working alongside my usual team, I’ve been inspired by all the healthcare workers I’ve met who are continuing to rise to the occasion.”

All across the country, many people have shown their appreciation of healthcare workers by donating food to hospitals, standing outside to clap or putting up signs that read “Thank you for keeping us safe.”

“Some days, we come home and just cry because that day was rough,” McSweeney said. “But seeing the support from the community is truly breathtaking.”

Mosser said that while there’s nothing that could have prepared anyone for working during a pandemic, the College’s nursing program gave her and her classmates much more than critical thinking, advocacy and teamwork skills — it gave them a supportive group of friends and colleagues.

“While we often feel overwhelmed, frustrated and scared during this time, I have also never felt a stronger bond between all people I work with,” Foglia said. “We are in this together and are all leaning on each other to get through this.”