By Michelle Lampariello, Elizabeth Zakaim, Miguel Gonzalez and Caleigh Carlson

Signal Staff

Kate McKinley (’11) does not trust her tap water. She triple filters her drinking water and uses another filter on her showerheads.

McKinley, an Ewing resident who was also in the running for town council last fall, started losing faith in Trenton Water Works’ — the local water filtration plant — ability to provide her with clean water after she continued to receive violation notices in the mail, which were similar to the letters sent to the College.

The most recent letter the College received from TWW regarding any violations was in February. TWW reported that it had failed to stay under the maximum contaminant level for two disinfection byproducts — haloacetic acids and trihalomethanes — within one year. According to the Centers for Disease Control, disinfection byproducts result when chemicals used to clean the water, such as chlorine, react with dissolved organic material in the water.

While TWW assured customers that this did not define an emergency situation and that no corrective actions, such as boiling water, were necessary, the plant mentioned that customers who are elderly, have a compromised immune system or drank water with excess levels of TTHM or HAA5 over many years may experience health complications and are at an increased risk for cancer.

Residents like McKinley found it aggravating to find out about these violations with so little accompanying information.

“I felt angry,” she said. “They notify us after high levels of anything toxic is detected and never give us any background on the potential danger of the elevated levels. You have to research that on your own.”

However, TWW provided information on how it is seeking to remedy the issue. According to the report, the plant has added a second permanganate feed line used to disinfect the water and is repairing the chlorine contact basins, which will result in the better removal of organics and reduce the amount of disinfection byproducts.

TWW would not comment publicly on its violations or solution policies.

TWW’s stiffness is part of why McKinley remains skeptical of the water quality, but not just for her own sake. Her friend, who has lived in Ewing for 20 years, has had breast cancer twice in the past 10 years. While neither can definitely say whether or not the cancer is correlated with the water quality, her friend represents those with compromised immune systems — the population whose health TWW warns might be at risk when drinking the water.

“She’s definitely at risk,” McKinley said.

Her friend uses filters for most of her water sources in her house and is still taking medication until doctors can safely report that she is in remission.

“She was very angry with the whole situation because of her immune system being compromised,” McKinley said. “This would only exacerbate her condition.”

For McKinley, her friend’s circumstance only added salt to a long-festering wound. TWW’s reputation was first tainted for McKinley four years ago when she was concerned about squatters living next door.

After reaching out to the town council for help with no luck, McKinley and her neighbors decided to take matters into their own hands. They called TWW to find out about the property’s last payments and learned that the residents had been delinquent for almost two years.

“It was a battle to get TWW to come out here and turn the water off,” she said. “The squatters buried the valve in concrete and TWW eventually had to bring in an outside contractor to shut the water off at the main.”

The incident created a health hazard, which then caused the town to board up the house and prevent future squatters. However, McKinley remained dissatisfied with TWW’s negligence.

“In this case, TWW could have prevented them from being able to live there had they shut the water off when payment was first delinquent,” she said. “But no one at TWW was watching. If any other person in my neighborhood didn't pay their water bill, it would be shut off immediately. This property, for some reason unknown to us, was treated differently.”

Because there remains such a concern surrounding the water quality in Mercer County, The Signal conducted its own water quality test and compared it to TWW’s most recent annual Consumer Confidence report.

The College also conducted its own test of the HAAs and TTHMs in October 2018 at different locations on campus, such as the Brower Student Center, Eickhoff Hall and other buildings.

The consultant group who conducted the tests at the College, Site Remediation Group, reported that the sample results did not detect any concentrations exceeding state drinking water standards.

For other measures of contaminants and disinfectants conducted by TWW, the College’s and The Signal’s own testing, see the tables below.

According to Amanda Radosti, the environmental programs specialist at the College, the results will vary between the TWW report and the SRG report in part because there are different sampling locations that are tested and because the concentrated amount that TWW tests at its plant gets distributed — and therefore less concentrated — when it reaches its large customer supply.

Similarly, TWW would report a lead violation at the specific sampling site it tested at, where levels of lead differ from the sampling sites the College tested through SRG, which explains why there is a lead violation in TWW’s report but not the College’s.

“Typically, (TWW) will sample at the curb before its going through (a) residence so it has more to do with their own distribution center and not at a personal residence where they have (lead pipes) installed,” Radosti said.

In 2018, TWW reported a violation of lead and turbidity. These violations occur when the plant has levels of these elements that exceed the governmentally established limits. Most of these elements are measured in parts per million or parts per billion.

Turbidity refers to the cloudiness of the water, according to the report, which can be caused by soil runoff or river sediment. The report said that high levels of turbidity can hinder the effectiveness of disinfectants and provide a medium for microbial growth. The highest level of turbidity, found in 2017, was 1.33 nephelometric turbidity units. According to the report, 95 percent of monthly samples must be at or below 0.3 NTU.

The report also said that TWW did not complete monitoring or testing for lead from Jan. 1, 2017 until Dec. 31, 2017 and for turbidity from Sept. 1, 2017 until Nov. 30, 2017. Because of this lack of data, TWW reported that it cannot be sure of the quality of drinking water during that time period.

TWW also experienced a failure of the combined filter effluent, used to measure turbidity, on Sept. 25 2017 that went unnoticed until Nov. 2 2017. This prevented TWW from providing data on the turbidity levels at the time.

TWW would not comment on the specifics of these or any other violations, but assured residents that there was no need for action.

“There is nothing you need to do at this time,” the report reads. “You do not need to boil your water or take other corrective actions. If a situation arises where the water is no longer safe to drink, you will be notified within 24 hours.”

TWW said in the report that it has repaired the damaged turbidimeter.

According to the 2018 report, out of the 119 samples collected in 2017 between January and June, 14 of those samples exceeded the action level for lead — 90 percent of samples were less than or equal to 17.6 ppb. The federal limit is 15 ppb. TWW reported “corrosion of household plumbing” as the potential source for this finding.

TWW, which gets its water supply from the Delaware River, released a pamphlet in July 2018 informing residents of this violation, the potential sources of lead and some solutions for residents to lower lead levels. According to the report, Trenton used lead in its water service lines until 1960 and in indoor plumbing until it was banned in 1986.

Up until 2014, brass fixtures, such as faucets, with eight percent of lead or less were allowed to be labeled as “lead free,” according to the report. Currently, that standard has been brought down to .25 percent of lead content.

According to the pamphlet, up until 1960 TWW used steel pipes lined with lead for water services to transport the water to customers.

“When treated water leaves TWW’s Filtration Plant, it is lead free,” the pamphlet reads. “The water mains in the street that transport water from the Filtration Plant are made mostly of iron and steel and do not add any lead to the drinking water. The lead from a home’s individual service line or plumbing effects only the tap water inside that home since water travels only one way in home plumbing.”

However, according to the 2018 report, TWW has recommended implementing corrosion control treatment and will replace at least seven percent of its lead service piping, a task for which the report said the plant has failed to proviwne a schedule. The plant also did not provide any documentation to the state indicating the number of lead service lines in its distribution system.

In order to reduce the negative health effects of drinking lead-contaminated water, which includes development impairment in children and kidney problems in adults, TWW recommends conducting lead tests, letting the water run for a few minutes before drinking or purchasing a water filter.

Violation notices are cause for concern for students at the College. Few students are willing to drink straight from their sink or a water fountain after campus-wide emails dated between October and February of this academic year announced the presence of haloacetic acids and trihalomethanes in the water. However, the state Department of Environmental Protection maintains that there are no toxic effects that can result from drinking the water at this time.

Larry Hajna, a press officer for the NJ DEP, explained that while prolonged exposure to these chemicals is shown slightly to increase the risk of developing cancer, the trihalomethanes and haloacetic acids are not in a high enough concentration above the federal limit to pose a risk to citizens as TWW works to remedy the issue.

“In TWW’s case, they were both just slightly above the standard, so they are basically getting customers these notices to let them know there’s an issue and they’re working to resolve it,” Hajna said.

Though water that came from TWW currently exceeds federal limits for disinfection byproducts, the DEP is not urging citizens to take any precautions because the federal limits are set well below the threshold for toxicity.

“The maximum contaminant levels for these chemicals are set to be very conservative,” Hajna said. “You would have to drink water above these levels for many, many years to slightly increase your cancer risk. We don’t tell people you can’t drink the water, because you can. It’s just that over an extended period of time, for many, many years, it may slightly increase cancer risk.”

David Hunt, a professor of organic chemistry at the College, agreed with the DEP’s conclusions. He explained that while TWW should work to remove disinfection byproducts from the water in a timely manner, the water accessible to the campus community at the moment is unlikely to do any harm.

Hunt was not surprised to hear that there are trihalomethanes or haloacetic acids in the water, and stated that it is close to impossible to remove these chemicals altogether.

“Chloroform (a trihalomethane) is a known carcinogen, but that does not mean that if there are trace amounts of chloroform that the water is bad for you,” he said. “It is possible to have trihalomethanes and haloacetic acids in the water that are well below toxic levels — it is hard to get rid of every last trace.”

Hunt believes that TWW’s disinfection byproduct violation is not unique to Mercer County, and should not be viewed as a threat to public health as long as TWW is working to resolve the issue.

“Anything above that normal level yet not in that toxic level is a cause for concern, but if you’re being notified by the water works that there’s an issue and they’re trying to deal with it, to me that’s acceptable. That happens in almost every municipality,” he said.

TWW has multiple options for going about reducing the level of disinfection byproducts in the water. Hunt posits that the company may use activated carbon treatments to help get rid of toxins.

Activated charcoal, which has gained increasing popularity in the health and beauty industries for the same reason, is known for its aboility to trap toxins and remove them from an unwanted area. By having the contaminated water travel through multiple passes of activated charcoal, Hunt proposes that TWW may be able to remove some of the trihalomethanes and haloacetic acids.

Both the DEP and Hunt said that time is one of the most important factors in arguing whether or not the disinfection byproduct violation can harm anyone who drinks the water.

“You probably are not going to get ill immediately, but there can be cases just like Flint,” Hunt said. “Repeated exposure to certain levels of toxins over a long period of time can cause irreparable damage.”

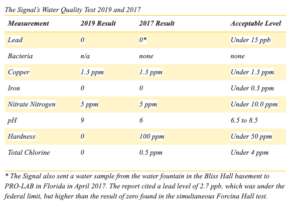

The Signal conducted an independent test of the water quality at the College, replicating its 2017 study, to determine the levels of contaminants including lead, pesticides, copper, iron, chlorine, nitrite nitrogen and nitrate nitrogen. The Signal did not retest for bacteria in 2019, though in 2017 there were no measurable levels.

Both tests were conducted using water from a fountain on the second floor of Forcina Hall using a home testing kit available online. The 2019 results were similar to 2017, but there were a few differences. See the chart below for the test results.

One aspect of the water quality that The Signal examined was the hardness, which is the amount of dissolved calcium and magnesium found inside the water.

According to the U.S. Geological Survey, hard water is high in dissolved minerals.

The site stated that water hardness is a result of the amount of dissolved calcium and magnesium. Water that is considered “hard” has higher amounts of primarily those two elements.

According to The Signal’s test, copper levels reached the federal limit, although according to the CDC, the level of copper in surface and groundwater is generally very low.

The ways that copper gets into drinking water are “either by directly contaminating well water or through corrosion of copper pipes if your water is acidic,” according to the CDC.

Alkalinity refers to the capability of water to neutralize acid. Because the definition is similar to that of pH, it is important to note the difference between the two. Water pH measures the amount of hydrogen — acid ions — in the water, whereas alkalinity is a measure of the carbonate and bicarbonate levels in the water.

According to Healthline, drinking alkaline water is somewhat beneficial, but can cause some side effects, including reducing natural stomach acidity that kills bacteria and prevents pathogens from entering the bloodstream.

Too much alkalinity may also agitate the body’s normal pH balance. Alkalinity and pH levels were two contaminants for which TWW said it did not properly test last year, according to the 2018 report.

The last portion of the test was for lead and pesticides, in which the results were under the federal limit. According to the Environmental Protection Agency, pesticides have the potential to contaminate drinking water supplies, as they are applied to farmlands, gardens and lawns, and “can make their way into ground water systems that feed drinking water supplies.”

TWW’s 2018 report gave pesticides “a medium susceptibility rating” in the Delaware River, but did not provide a numerical level of potential contaminant levels in the water.

The EPA also said that whether these contaminants pose a health risk depends on how toxic the pesticides are, how much is in the water and how much exposure occurs on a daily basis.

The Signal’s results in this portion of testing were at zero.

Most students at the College have taken on a cautionary approach to the drinking water.

Senior early childhood urban education and psychology dual major Serina Grasso, who lives in Hausdoerffer Hall, said she relies on her Brita filter for clean water.

“Even though I drank tap water for most of my life, I prefer to use the Brita filter for my water just to be safe,” she said.

Senior marketing and international studies double major Karley Panek, who shares an off-campus house in Ewing, added that she and her housemates do not feel safe drinking the water from tap and that they also use a Brita filter for their water.

“Of course I use it to brush my teeth, or wash my face, because I don’t think it’s overly concerning to use it,” she said. “I just prefer not to drink it.”

Senior English and communication studies double major Hope Simiris, who is a Campus Town resident, also strays from the school’s main water source.

“I personally drink bottled water mostly, because I feel the safest drinking that,” she said.

Radosti, who drinks the tap water at the College, conducted her own “pseudo-experiment” while she water tended at the Water Bar, an art gallery exhibition that visited the Art and Interactive Multimedia Building back in February, to challenge student apprehensions about the water quality.

Visitors of the bar were encouraged to drink water from three different locations and were then asked to try to decipher where each sample was from –– the College, Philadelphia or Horsham, Pennsylvania.

According to Radosti, students came in confident that they would be able to tell which sample was from the College.

“Students would say, ‘Oh the water here is terrible. I’m gonna absolutely know which one it is,’” she said. “Nobody got it.”

According to Radosti, the poor reputation surrounding the College’s water quality is based mostly on perception, which she was glad to help try and debunk for students.

“We don’t have the lead pipes. We don’t have the lead soldering. We don’t have the lead fixtures,” she said. “We don’t have those things that really cause concern.”

Despite those reassurances for students at the College, Ewing residents remain skeptical of TWW’s ability to provide adequate service to its customers. Many residents like McKinley feel more comfortable taking matters into their own hands.

“As a resident of Ewing, I'm angry and frustrated,” she said. “We just received another letter about a month ago, so I don't anticipate this problem being resolved any time soon. Filters are about the only way you can deal with this, as boiling the water does nothing.”

Although she was not elected a position on the council, McKinley said that TWW was one of the main reasons why she decided to run for a position.

McKinley hopes that the new leadership at TWW, with former Trenton Mayor Shing-Fu Hsueh as the new director, will eventually change its operating methods, though her expectations are low.

“The leadership change hasn't really influenced my impression of TWW,” she said. “You have to be tough and you have to be smart. Trenton requires political brawn. If he cannot navigate that, then he won't succeed.”