By Jane Bowden

Features Editor

National Poetry Month is a time to reflect on famous poets, such as Maya Angelou and Langston Hughes, who have highlighted important social issues in their creative works.

In an April 1998 issue of The Signal, Derek Walcott, a Nobel Peace Prize-winning poet and playwright, read his poem, “Omeros,” and spoke to students at the College about the inequalities that African-Americans face.

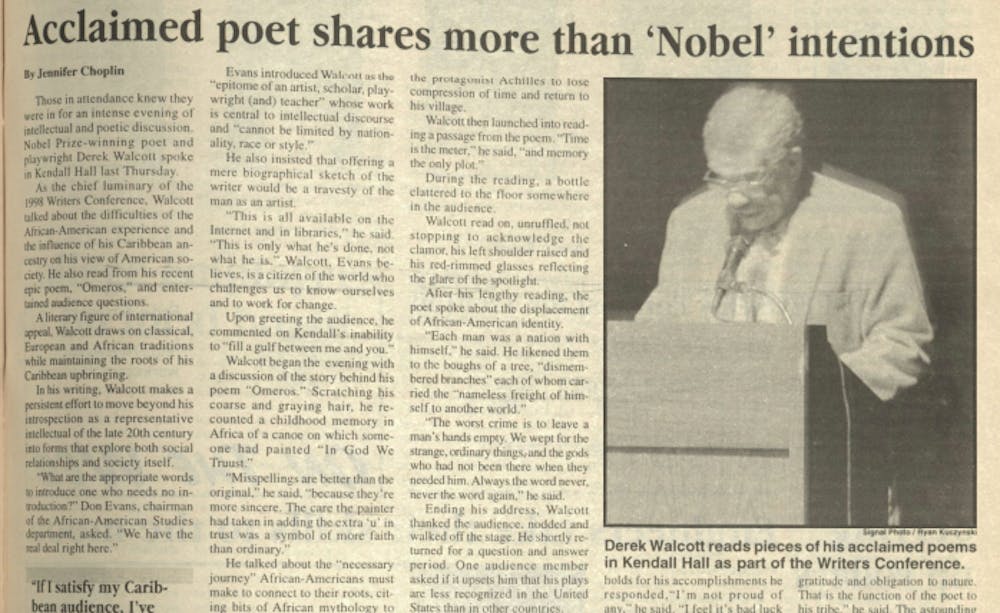

Those in attendance knew they were in for an intense evening of intellectual and poetic discussion. Nobel Prize-winning poet and playwright Derek Walcott spoke in Kendall Hall last Thursday.

As the chief luminary of the 1998 Writers Conference, Walcott talked about the difficulties of the African-American experience and the influence of his Caribbean ancestry on his view of American society. He also read from his recent epic poem, "Omeros," and entertained audience questions.

A literary figure of international appeal, Walcott draws on classical, European and African traditions while maintaining the roots of his Caribbean upbringing.

In his writing, Walcott makes a persistent effort to move beyond his introspection as a representative intellectual of the late 20th century into forms that explore both social relationships and society itself.

"What are the appropriate words to introduce one who needs no introduction?" Don Evans, chairman of the African-American Studies department, asked. "We have the real deal right here."

Evans introduced Walcott as the "epitome of an artist, scholar, playwright (and) teacher" whose work is central to intellectual discourse and "cannot be limited by nationality, race or style."

He also insisted that offering a mere biographical sketch of the writer would be a travesty of the man as an artist.

"This is all available on the Internet and in libraries," he said. This is only what he's done, not what he is. Walcott, Evans believes, is a citizen of the world who challenges us to know ourselves and to work for change.

Upon greeting the audience, he commented on Kendall's inability to "fill a gulf between me and you."

Walcott began the evening with a discussion of the story behind his poem "Omeros." Scratching his coarse and graying hair, he recounted a childhood memory in Africa of a canoe on which someone had painted "In God We Truust."

"Misspellings are better than the original," he said, "because they're more sincere. The care the painter had taken in adding the extra 'u' in trust was a symbol of more faith than ordinary."

He talked about the "necessary journey" African-Americans must make to connect to their roots, citing bits of African mythology to support his position. A bird called the sea swift connects the two worlds in the poem "Omeras." The sea swift represents the joining of the middle passage, taking a canoe back to Africa in an instant.