By Camille Furst

News Assistant

The School of Humanities and Social Sciences and the Women in Learning Leadership program sponsored a seminar titled “The Gangster: From Ancient Archetype To American Obsession,” on Oct. 8 in the Library Auditorium.

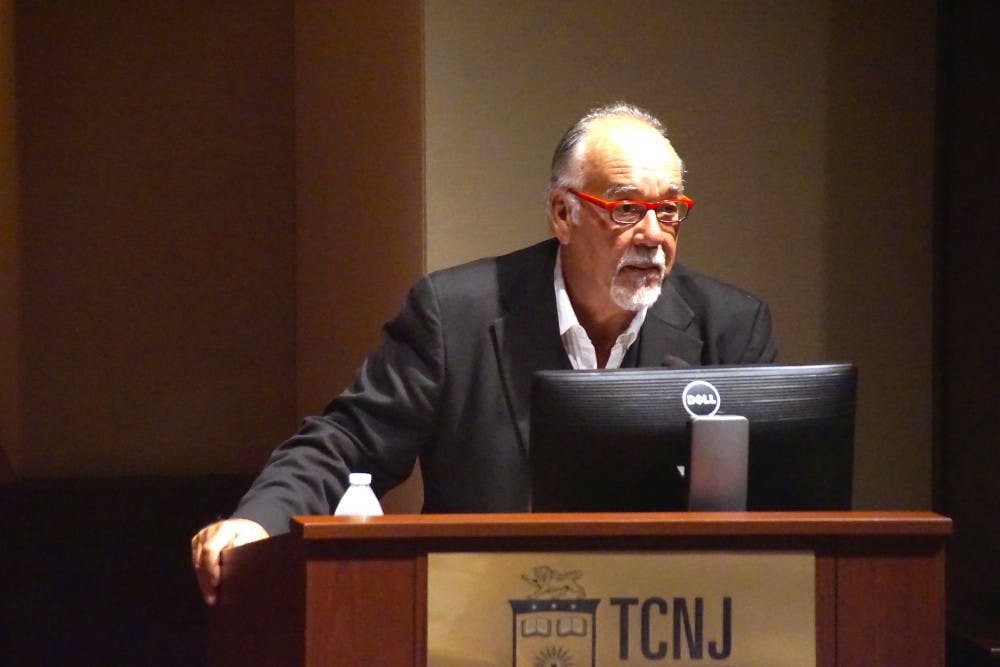

With the help of Fred Gardaphé, a professor of English and Italian-American studies at Queens College, the event taught students how and why the gangster figure has become so prevalent in the U.S., why gangsters are stereotypically portrayed as Italian-American and how it reflects manhood in American culture.

Gardaphé, who has conducted research for more than 30 years and written multiple books on how the gangster became a pivotal and influential American icon, grew up in Melrose Park, a predominantly Italian-American suburb of Chicago.

He began his speech by discussing his personal connection to the topic of gangsters. Recalling his life in Chicago, Gardaphé felt personally affected by the violence of gangsters.

“Living in a neighborhood of Chicago, violence was not only common, but expected,” Gardaphé said. “If it were not for reading, I would’ve become a gangster. This I know for a fact.”

In high school, he began researching about the Italian mafia, specifically the Valachi Papers, a book chronicling the lives of real mafia members.

Gardaphé recalled one moment at a work party for the restaurant where he was employed when his boss asked him what he was reading and he replied, “The Valachi Papers.” As it turned out, Gardaphé’s co-workers were members of his neighborhood’s mafia and he was staring at the same people he was reading about.

“Everyone stopped talking and turned to look at me,” Gardaphé said. “I immediately realized that there were men in that room who had their names in that book.”

Once Gardaphé realized how connected he was to the mafia, he further pursued his interest in researching the historic figure of the gangster.

After his years of research, Gardaphé came to the conclusion that the figure of the gangster is ingrained in the history of American culture.

“The gangster represents the last stand for patriarchy in America, and a chance for Americans to live in an unknown past as we head into an unknown future,” Gardaphé said.

He further argued that the gangster figure was always molded to fit whatever pleased the American public the most. Films such as the Godfather portrayed the gangster as a heroic protagonist –– gangsters in the U.S. then imitated this representation.

“The real gangster started imitating the characters in the Godfather films,” Gardaphé said. “After a generation, you could hardly tell the difference between the real and the artificial gangster.”

The transformation of fact into fiction and vice versa led Gardaphé into a discussion about why the Gangster has always played such a pivotal role American culture.

He said that the gangster figure has been previously portrayed as a hero who overcomes poverty, discrimination and other societal bias. With popular Italian-American gangsters such as Al Capone rising out of poverty, Gardaphé claimed they “captured popular imagination” throughout the U.S. The legacy of these valiant gangsters were cemented in films and television shows during the 1990s and 2000s with movies such as Goodfellas and shows like the Sopranos.

“The figure that first appeared in newspaper reels and newspapers of the 1920s has grown to heroic proportions,” Gardaphé said. “Americans –– especially Italian-Americans –– must understand why contemporary America needs the gangster, and why it needs to be an Italian-American.”

Gardaphé explained how Americans have singled and labeled foreigners as the antagonists. He explained that during the 1980s, Former President Ronald Reagan would call the Soviet Union the “evil empire.”

Gardaphé also explained how the figure of the gangster continually reflected cultural perceptions of manhood. The gangster figure, as portrayed through the media as a hero rising from poverty, transformed the ideal masculinity of male honor to violence and aggressive behavior.

“After all, for centuries, a man’s honor was measured in terms of his ability to deal with violence,” Gardaphé said.

Gardaphé stated that this misrepresentation of manhood has played a role in his personal life as well.

“Many of us young Italian-American boys became so infatuated with the attention given to Italian-American criminals that we found our ways of gaining that notoriety and power,” he said. “I want men to think differently of themselves.”