By Elizabeth Zakaim

Reviews Editor

The first time freshman journalism major Dylan Calloway wondered about the College’s water quality was when he saw a picture of a moldy pipe near Eickhoff Hall on TCNJ.snap. This inspired him and several other students to research further into the College’s water quality, as part of a group project for their journalism class, Writing for Interactive Multimedia.

“It was just to raise awareness,” Calloway said. “If someone becomes aware, then they might spread (that concern) to somebody else, and we’ll all become more well aware.”

With videos of Flint, Mich., citizens setting their water on fire, students have become concerned about their own drinking water quality. The issue in Flint sparked pushes for lead testing in institutions nationwide, including the College.

Heidi Cho, The Signal’s news assistant and a freshman journalism major who is in Calloway’s journalism class, was shocked when Calloway spoke about the picture of the moldy pipe on campus, so she tried to do some digging.

The pipe, located near Eickhoff Hall, appeared severed, and while Cho doesn’t know if it had ever served the College, she and her classmates are continuing to research the process of how the College’s water is treated and filtered.

“We talked to a professor about the water quality here on campus… and she led us towards the issue of pollution coming from storm run-off drains,” Cho said.

She learned that any chemicals in the water running off of cars in a rainstorm down through unfiltered storm drains and later through the Delaware River could eventually reach their drinking water. What the group hadn’t realized was the middle step in the process –– Trenton Water Works, the local water filtration plant.

The College’s water comes from TWW where water is treated and filtered before it arrives to the school. TWW Superintendent William Mitchell said impurities found in pretreated water often come from farm runoff. This includes fecal matter, herbicides, pesticides, fertilizer and storm water discharge. During the winter, for example, chloride levels in the water increase after a lot of salting for snow and ice.

TWW treats and filters its water before it reaches local tap, according to Mitchell. The filtration process involves flash mixing of treatment chemicals to the water, coagulation, flocculation and sedimentation –– small solid particles, or flocs, stick together and become heavier in the water and begin to sink to the bottom. These impurities are then removed from the water.

Following public concerns about contaminated drinking water in the New Jersey area, the College hired EnviroTrac, an environmental consulting and contracting firm, to sample and evaluate the water quality.

The company took samples of lead and copper from lines entering campus directly from TWW, such as all on-campus dining locations and athletic fields. The analysis did not detect any concentrations of pollutants at or above the state and federal limit, according to EnviroTrac’s report summary.

As of 2015, Trenton public schools reportedly did not contain any lead in their water, according to NJ Future, a nonprofit organization that promotes infrastructural and environmental redevelopment. Yet in an NJ.com article from 2016, 26 samples from 10 schools were found to have lead levels as high as 100 parts per billion.

According to a 2016 Trentonian article, the New Jersey Department of Health published a Childhood Lead Poisoning report in 2014, which stated that out of the 3,421 tested in Trenton and other state municipal agencies, 6.3 percent of children under the age of six had elevated blood levels higher than children in Flint, where about 3 percent of children had elevated lead levels.

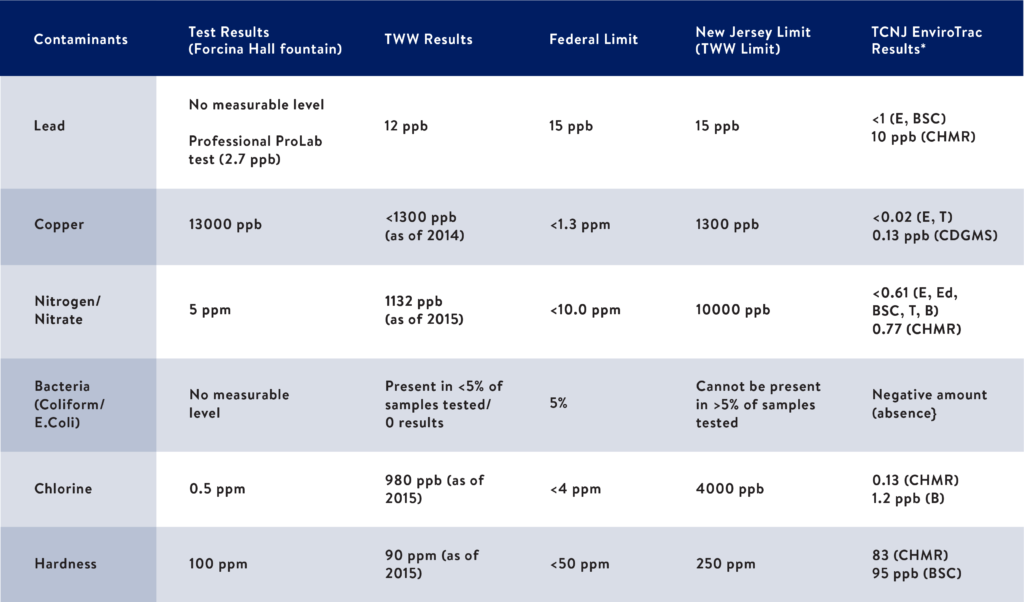

The Signal sent a water sample from the water fountain in the Bliss Hall basement to PRO-LAB in Florida on April 17. The report cited a lead level of 2.7 ppb. The federal limit for lead levels is 15 ppb.

The Signal also conducted its own water quality test on Feb. 20 using a water fountain on the second floor of Forcina Hall. The water did not have any measurable levels of lead, pesticide or bacteria.

The total chlorine level reached 0.5 parts per million, which is under the federal limit of 4 ppm. Nitrate nitrogen levels were at 5 ppm, which is under the federal limit of 10 ppm. The test found a copper level of 1.3 ppm in the water, which just meets the federal limit. There were no levels of iron found in the water, and the pH level of 6.0 was under the federal limit.

The hardness level of 6 grains, or 100 ppm, found exceeded the federal limit of under 50 ppm, yet the maximum contaminant level cited by TWW is 250 ppm. As of 2015, TWW reported having 90 ppm in its water, which was not deemed a violation.

Both the Bliss Hall Annex and Forcina Hall were built in 1979 and 1969, respectively, said Luke Sacks, the College’s head media relations officer. Most homes that were built before 1986 are more likely to have lead pipes, according to the United States Environmental Protection Agency.

However, the College is not aware of lead pipes in its buildings, according to David Muha, the College’s spokesperson.

Keith Pecor, an associate professor and department chair of biology whose research focuses on freshwater ecology and invertebrates, said all he can conclude from The Signal’s assessment is the state of the water quality specifically in the Forcina water fountain, not the College’s water quality as a whole.

The fountain’s hardness level is due to calcium and magnesium, according to Pecor. The disadvantages of too much water hardness are primarily aesthetic — it might require more soap or water softeners during laundry and can contribute to scaling in industrial equipment, but hardness is not considered a health risk under the Environmental Protection Agency’s standards.

However, the state of New Jersey has had health risks from its water in the past.

One contributor to New Jersey’s industrialization and prosperity was Ciba-Geigy, a company that manufactured chemical dyes in Tom’s River, N.J., from 1952 to 1990. Although, as Dan Fagin documented in his book “Tom’s River: A story of science and salvation,” that prosperity had downsides: The company was dumping toxic waste chemicals into aquifers that polluted the town’s drinking water, which may have contributed to childhood cancers among other diseases.

New Jersey’s water quality continues to pose problems. New Jersey is still in the midst of cleaning its lakes, rivers and other bodies of water more than 40 years after the Clean Water Act was passed, according to a 2014 article from NJ.com. The EPA cited more than a thousand instances of contaminated water across the state, NJ.com reported.

The struggle for better water comes from the efforts of organizations like Isles, which provides services aimed to help the Trenton, N.J., community. Its efforts include lead testing in community homes and educating local citizens on environmental issues.

Isles Managing Director Pete Rose recommends replacing lead fittings with inline filters in drinking fountain pipes to prevent lead from dissolving into the water at schools.

“(This is) cost effective and easy to do,” Rose said.

Because of federal regulations, the risks to water quality are not what they used to be. Nicky Sheats, director of the Center for the Urban Environment at Thomas Edison State College, researched water pollution before her focus shifted to air pollution.

Sheats said both forms of pollution contributed to the phenomenon of acid rain that gained a lot of national attention during the ’80s and ’90s.

According to the EPA’s website, both sulfur dioxide and nitrogen oxide were gases emitted from different industry power plants across the country. Sheats said when contaminated with these elements, rain would flow into surface water, making it more acidic and dangerous to consume.

The EPA established the Acid Rain Program in 1995, which offered incentives to power plants to reduce emission. By 2010, emissions were reduced to about one-half of what they were in 1980.

Despite past and present attempts at improving the water quality, Sheats’ biggest fear has become the Trump administration’s role in environmental protection.

*This information was provided by the College’s spokesperson David Muha, who read from EnviroTrac’s data report.

Key: CHMR = Cromwell hall mechanical room, CDGMS = Cromwell/Decker garage mechanical space, E = Eickhoff Hall, BSC = Brower Student Center, T = T-Dubs, Ed = Education Building, B = Business Building (Jason Proleika / Photo Editor)

“We’re really afraid that (the president) is going to cut back on existing laws that’s become a bedrock of environmental protection,” Sheats said. “I’m worried about the Clean Air Act and the Clean Water Act.”

President Donald Trump signed an executive order that will allow him to essentially roll back on regulations under the 1972 Clean Water Act, according to an NBC news article published in March.

This includes former President Barack Obama’s 2015 clean water rule, which gives the federal government the right to limit pollution in major bodies of water and other streams that flow into larger waters.

The rule stirred some controversy, according to the article, regarding the federal government’s right to exert such broad authority. Rural organizations like the American Farm Bureau Federation have been against the rule, as they argue it forces them to apply for federal permits to use fertilizer near streams that might flow into larger bodies of water.

While Trump’s legal orders may take longer than his term to be put into action, a more lenient prohibition on water pollution will make filtering and treating water an even more critical process.

Rose is most worried about the administration cutting back funding from the EPA and other environmental agencies. Those cuts won’t just threaten the health of the communities Isles is trying to help, but it will likely hurt “the health and well-being of all Americans.”

Cho believes that the government should continue to focus on environmental issues.

“I think that if the laws were more lenient, businesses would take the most cost-effective option to getting rid of waste, which is usually to the detriment of the ecology of the surrounding areas,” she said.

It’s important to take care of local communities and be mindful of the potential damage people can cause, according to Mae Calacal, a junior journalism major who is Cho’s and Calloway’s classmate.

“The fact that (government) funds will be cut shows that these issues are not of great concern to these major figures,” Calacal said.

This is issue is not just in the hands of anonymous public officials –– it is the average citizen’s responsibility, too.

“It should definitely be focused on more,” she said. “What happens in the environment affects everyone.”