By Chelsea LoCascio

Managing Editor

When swatting bugs, wiping away sweat and moving fallen bamboo culms to clear a path, it can be easy to forget you are still at the College.

The on-campus bamboo forest behind Green Farmhouse is littered with food wrappers, beer cans and water bottles full of green liquid — signs that this spot has hosted the occasional “good time,” according to a Signal article from Sept. 24, 2008.

That same article reported that the only exposure Thomas Hasty, former head grounds worker for the Office of Grounds and Landscape Maintenance Services, had to the bamboo was limited to the few times the grounds crew needed to clean up the litter, along with some cult-like paraphernalia reminiscent of “The Blair Witch Project.”

This campus oddity has been shrouded in mystery, as Hasty had reportedly never learned why the bamboo was there, and any further knowledge left with him when he retired.

According to Head Media Relations Officer Tom Beaver, the mystery continues.

“We do not have a record of when the bamboo was planted and why, at that time, the decision was made to plant bamboo,” Head Media Relations Officer Tom Beaver said.

Eight years later, the College still has no idea.

Until now.

The Eldridge family

Walk along the Metzger Loop away from the bamboo forest behind Green Farmhouse — past the Administrative Services Building and before the apartments — and one can spot another patch of bamboo. Unlike the bamboo behind the farmhouse, this one has a sign posted in the patch.

The marker indicates a few critical points: the Eldridge family planted the bamboo at this specific location in the early part of the last century, and it was the first bamboo planted in Ewing, N.J.

It also notes that Eldridge Park in Lawrenceville, N.J., was named after the family and that one family member named John was an associate of William Penn: “English Quaker leader and advocate of religious freedom, who oversaw the founding of the American Commonwealth of Pennsylvania,” according to britannica.com.

The Rockino family were the ones who acquired the Eldridge’s property on Pennington Road — they believe it was built around 1919 — in an estate sale in November 1973. Linda Rockino Schultz, 64, does not live in this house, but her brother does.

According to Rockino Schultz, Sarah Eldridge built a colonial home for her son, C. Wellington Eldridge, and in the yard, she planted several species of flora still there today, including Silver Spruce, Japanese Maple and bamboo. Their fence is the one that separates the College from the bamboo patch.

A not-so-invasive species

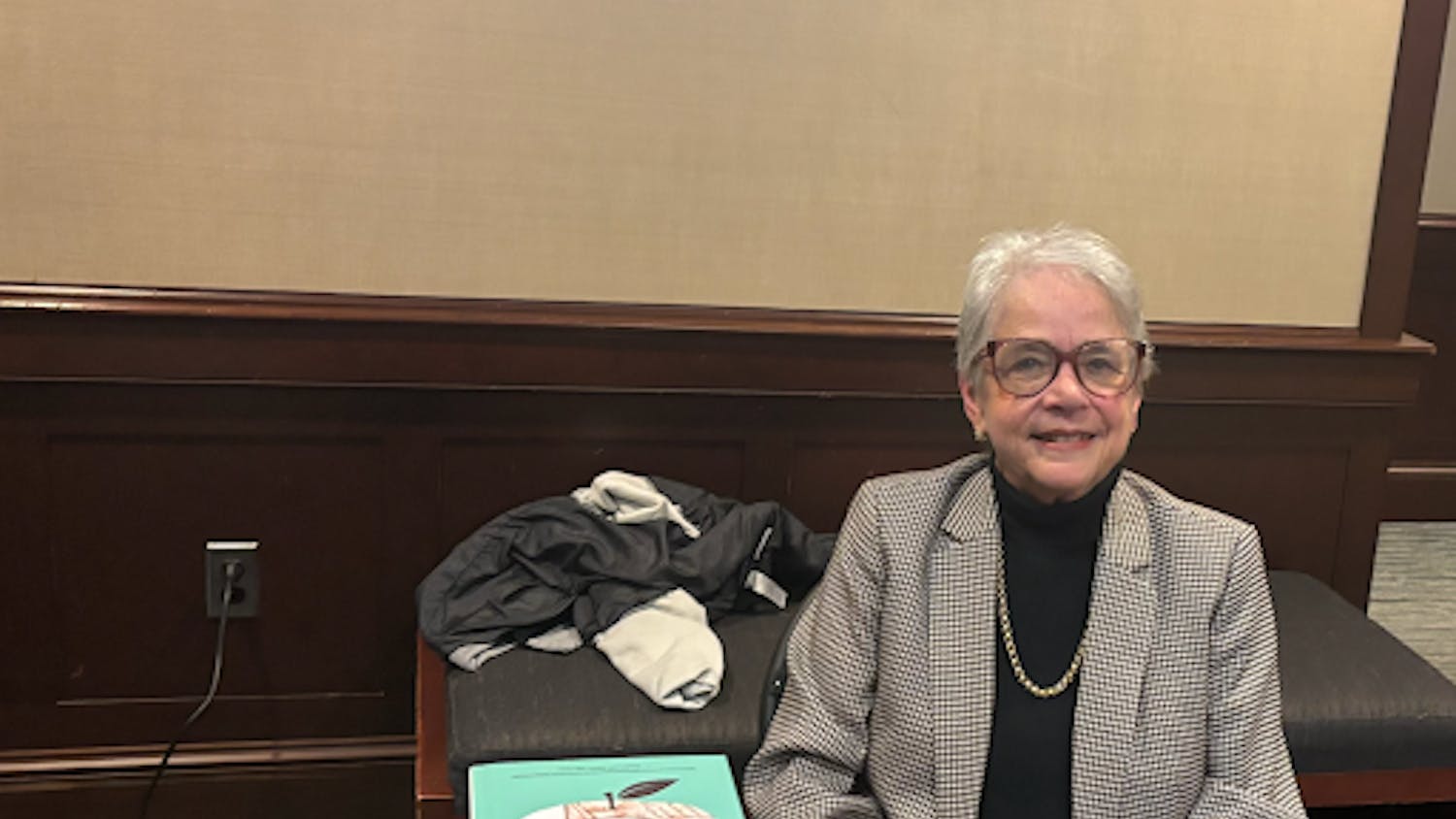

So, what is the connection between the Eldridge’s bamboo and the College’s? The answer can be found in basic ecology, according to Professor of Biology Janet Morrison, who is currently conducting her own research on the interactions between overabundant deer, invasive species and native plant communities.

Morrison said the bamboo on campus is likely Golden Bamboo, since that is the most common type of planted bamboo.

“(Golden Bamboo) might flower (about) every five to 10 years,” Morrison said. “So, it’s possible that a few seeds made it and got spread to the other side of the road, and so it’s making a second patch.”

That second patch has been growing just over the fence and down the road on the College’s campus.

Since John Eldridge was the one to introduce the plant, which, according to Morrison, is commonly found in Asia, the bamboo is actually an invasive species.

“Generally, when we say ‘invasive species,’ we’re usually talking about species — whether they’re animals, plants, whatever — that come from a different continent and have been introduced to a new continent either intentionally or accidentally,” Morrison said. “(The species) have done very well in the area over a quite short period of time — in ecological time rather than, say, evolutionary time.”

Morrison said the bamboo has survived here because it thrives in temperate climates, as opposed to harsher ones in the arctic and tropics, for example.

While often beautiful and exotic, invasive species are not necessarily positive for the local native plants. Some invasive species can spread out and inhibit native species from growing, which can lower biodiversity. These species can affect the soil’s nutrients and the local water cycle, as well, according to Morrison.

“If someone plants a little bamboo in their yard and it takes there — does well — it will then send out stolons, or these little… horizontal stems, basically, and these sort of spread out and make a giant clump,” Morrison said. “On a very, very local scale where it’s spreading out every year and making little bit of bigger and bigger clumps, it’s forcing out other plants that are there.”

Fortunately, bamboo is not a huge threat, as it grows tall quickly, but spreads out slowly.

“People consider it invasive, but from my perspective — compared to so many other species — it’s not of particular concern,” Morrison said. “It does not act like a classic invasive species… You don’t see bamboo invading across all of our forest patches on campus.”

To Morrison, the bamboo on campus is symbolic of a much larger issue — the decrease in species diversity.

“Bamboo is very dramatic, and people notice it because it’s so big and incredible looking,” Morrison said. “As the world is becoming more globalized… we’re losing diversity of different species… because of the success of a relatively small number of cosmopolitan species that are well-adapted to the sort of disturbed environments that people make. As people cover the globe, those are the species that are going to do well.”