By Jessica Ganga

News Editor

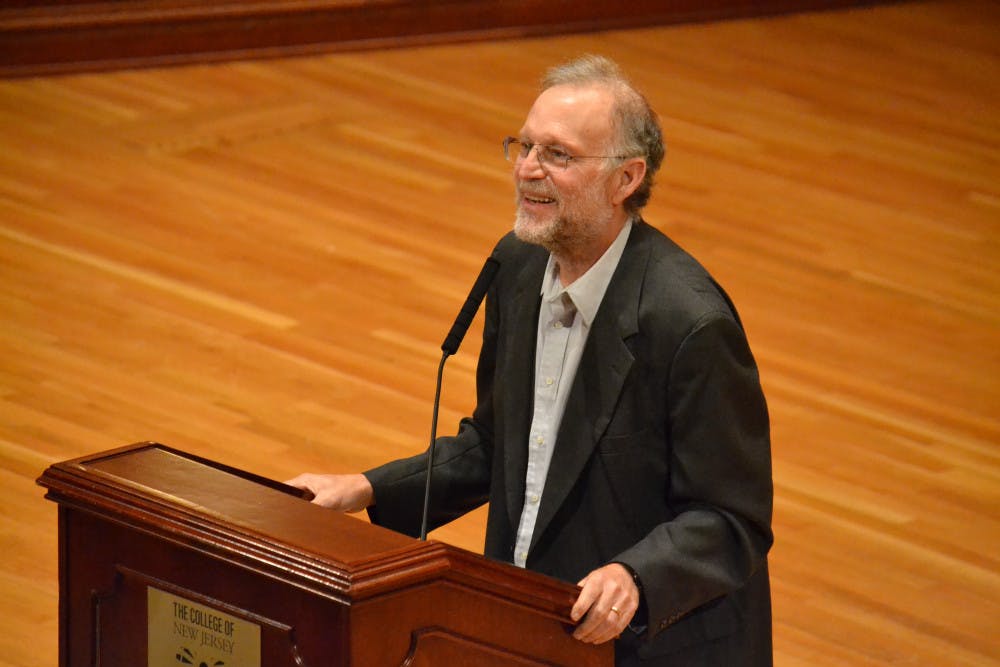

For Jerry Greenfield of the famed Ben & Jerry’s ice cream, getting into the ice cream business was not part of his plan.

During the College Union Board’s Fall Lecture in Mayo Concert Hall on Tuesday, Oct. 18, Greenfield told the story of how the company that began in a used gas station eventually grew into a multi-million dollar ice cream business.

Greenfield and his business partner, Ben Cohen, grew up in Merrick as childhood friends in Long Island, N.Y. The pair went their separate ways after high school.

While Cohen worked odd jobs and took a less conventional approach to life and education, Greenfield aspired for academic greatness, but was rejected from every medical school to which he applied. This led them to join together and begin their own business.

“There we were, failing at everything we were trying to do,” Greenfield said. “Ben and I said to each other, ‘Why don’t we try being something that’s fun — be our own bosses? Since we always liked to eat, we should do something with food.’”

With knowledge from a cheap ice cream making course at Pennsylvania State University and $4,000 saved between them, Cohen and Greenfield moved to Burlington, Vt., — a town without an ice cream parlor.

From there, they created a business plan in order to receive an $8,000 bank loan. To their surprise, the bank lent them the money, and the two worked on opening their shop.

Ben & Jerry’s started small by distributing ice cream in pint-sized containers to mom-and-pop grocery stores. Eventually, the company attracted the attention of large distributors from Boston and Connecticut.

“It was the first time we were going to be selling ice cream into major markets,” Greenfield said.

Soon after the trucks started carrying their ice cream, Cohen and Greenfield were told that the Pillsbury company, which owns Häagen-Dazs ice cream, didn’t want the distributors to carry Ben & Jerry’s. They had found their first competitors.

“I made my way to Minneapolis — to the Pillsbury Headquarters — where I was a one-person picket line,” Greenfield said. “I was walking up and down the sidewalk in front of Pillsbury Headquarters. I had a picket sign that said, ‘What’s the Dough Boy afraid of?’”

They had multiple tactics and recruited their faithful consumers to help them with the campaign to get their ice cream back on the distribution trucks. The story was picked up by major newspapers like The Boston Globe, so Häagen-Dazs backed down.

“That’s what permitted Ben & Jerry’s to distribute across the country,” Greenfield said.

As their business grew, Cohen and Greenfield realized they were turning into businessmen — a new and uneasy feeling. This changing role almost led them to leave their business behind. However, convinced by a friend to continue, the two chose to grow their business, with a few unique quirks. They needed more funding, but went about it in a non-traditional way.

“We said, ‘What we would like to do is use this need for cash that the business has and use it to have the community become owners of the business, so that as the business prospered, the community as owners would automatically prosper,’” Greenfield said.

By holding a public offer, Cohen and Greenfield raised $750,000 and one out of 100 families in Vermont became owners of Ben & Jerry’s.

After local success, Cohen and Greenfield expanded the offer to the national level, and they established the Ben & Jerry’s Foundation, another way for them to give back to the community.

“The foundation would receive 7.5 percent of the company’s pre-tax profits,” Greenfield said. “That was the highest percentage of any publicly held company. The reason we chose such a high percentage was that our feeling at the time was… if we wanted to be as much (of) a benefit to the community as possible, we should give away as much money as possible.”

In no time, the foundation began receiving grant requests from nonprofit organizations that supported those struggling with issues like hunger and housing.

Greenfield found that the best way to run their business was to figure out the important components of the Ben & Jerry’s plan and integrate it with social and environmental issues. This idea proved to be easier said than done.

“It’s sort of like any process of innovation and figuring out something that you don’t know how to do,” Greenfield said. “It’s a matter of coming up with some ideas — you try them, usually they won’t work, you try and learn from that and you make changes, and you try again. Eventually, through trial and error, you get things figured out. That’s the way you learn how to do things.”

The company discovered Greyston Bakery in Yonkers, N.Y., a nonprofit pastry shop that provided jobs and job training for impoverished people.

“Ben & Jerry’s came up with a flavor, Chocolate Fudge Brownie, using brownies from the Greyston Bakery,” Greenfield said. “Ben & Jerry’s bought over $5 million worth of brownies from Greyston.”

Greenfield and Cohen continued to look into ways to help their customers.

Now, the company owns about 250 franchises, 14 of which are PartnerShops, or stores that are owned and operated by nonprofit social service agencies that work with at-risk youth.

“For those agencies that own Ben & Jerry’s shops, any money they make goes into funding their programs,” Greenfield said. “At the same time, they provide job training and jobs for (all) the people they work with.”

Along with their charitable ventures, the two are vocal about pressing issues in the country, such as democracy, environmentalism and social justice, and the company recently offered a statement on the Black Lives Matter movement.

In an interview with The Signal, Greenfield said that with their platform, large companies have the opportunity to show support on important issues.

“The feedback that Ben & Jerry’s got for that statement was overwhelmingly positive and it may be because of the people that follow Ben & Jerry’s or eat Ben & Jerry’s ice cream are more supportive of that,” he said. “I think most businesses (don’t) do it because they don’t want to take a risk… Their primary purpose is to make money and they don’t want to do anything that interferes with that.”

Despite the company’s successful charity work and stance on important issues, the pair still received criticism — a bizarre response, according to Greenfield.

“Several years ago, Ben & Jerry’s started to get criticized in the media that we were trying to convince people to buy more ice cream in a cynical (way) by doing good deeds,” he said.

The two responded to the media backlash in the best way they knew how — with positivity that highlighted their core beliefs.

“Probably most important of all, it helps with building a deep and genuine bond with our customers over shared values,” Greenfield said. “What we’ve been learning at Ben & Jerry’s is there is a spiritual aspect in business just as there is a compliance of individuals. As you give, you receive. As you help others, you are helped in return.”

No matter what, the company will stick to its business plan to incorporate its most valued beliefs and serve its community.

“We’re all interconnected and as we help others, we can’t help be helped in return,” Greenfield said. “For business and people, it’s all exactly the same.”