By Erin Cooper

Staff Writer

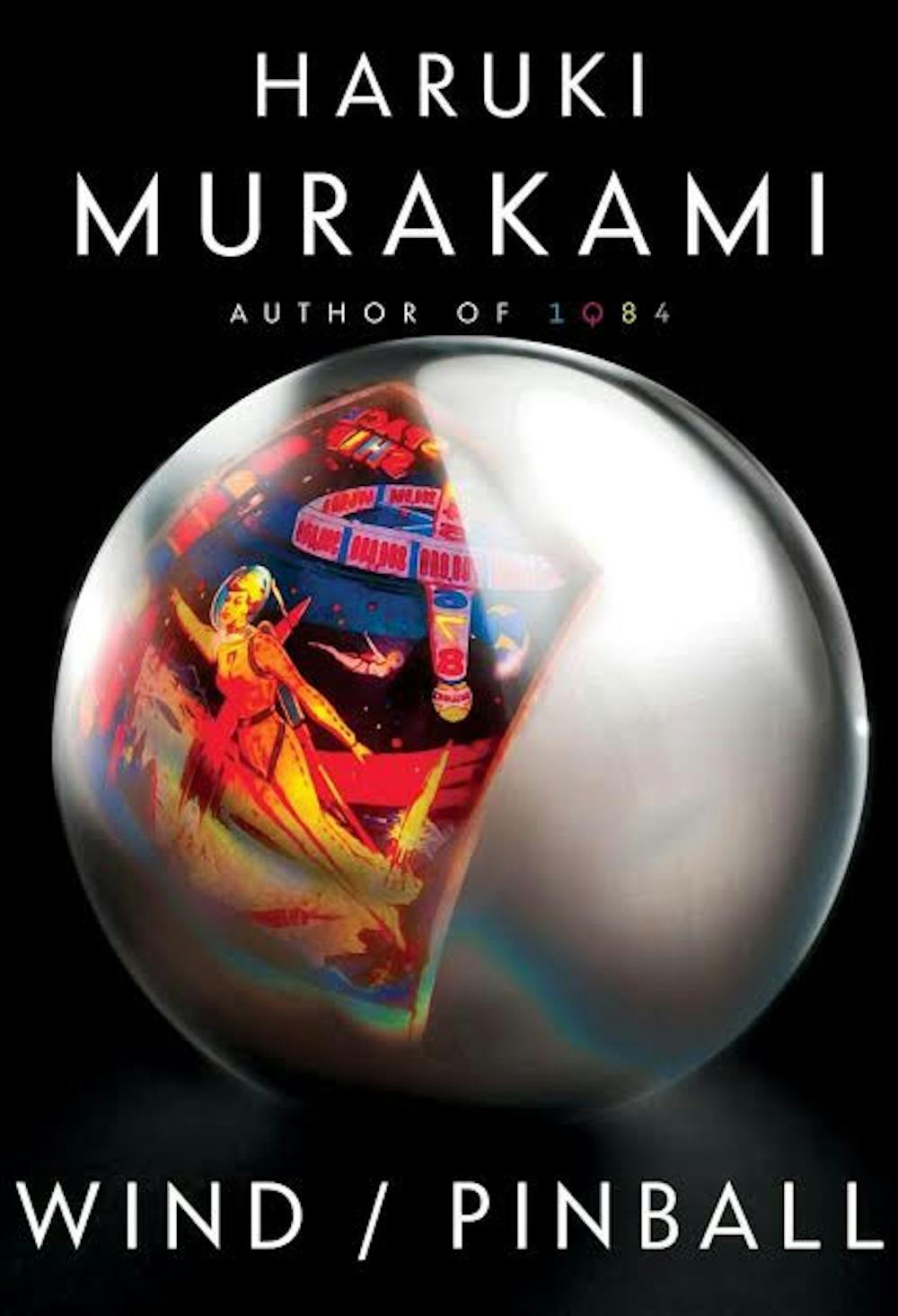

The latest U.S. release from Japanese contemporary writer Haruki Murakami isn’t exactly new, but then again, it is. The two stories that comprise “Wind/Pinball” are from his previous novels, “Hear the Wind Sing” and “Pinball, 1973.” This new release combines these critically acclaimed novels and includes a new translation by Ted Goossen as well as a special introduction from Murakami.

“Wind/Pinball” will be difficult for admirers of Murakami to resist, and is worthwhile reading for those who aren’t familiar with the author, although it may not be the best place to start.

“Norwegian Wood” or “The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle” are some of Murakami’s more recent and popular works, and while there is charm in the idea of starting at the beginning, this book certainly has its merits.

“Wind/Pinball” is an intriguing document of a writer developing his style and themes. In the introduction, Murakami describes the origin of his creative drive when he writes, “For no reason and based on no grounds whatsoever, it suddenly struck me: I think I can write a novel.”

These stories are the result of that impulse. Their progression charts Murakami’s growing skill and confidence as he embarks upon his quest to become a novelist, a quest as sudden and inexplicable as the voyage of any Murakami character. It is learning the story behind the novels that makes “Wind/Pinball” truly special.

Murakami’s novels are ghost stories haunted by loss. In “Wind,” the reader is introduced to the unnamed narrator and his disreputable friend, the Rat, as they hang around J’s bar, philosophize over french fries, leave people and are left behind. The back-and-forth dialogue is peppered with references to film, literature and music — from Beethoven to the Beach Boys.

“Wind” is a slice-of-life story with traces of the unknown and unknowable. There is an almost ephemeral lightness to it. As our narrator faces an uncertain future, his past returns to him in glimpses. It is in the odder glimpses that the story finds its identity.

“Pinball,” the second novel, reveals more of a developed Murakami. The narrator and the Rat return in this story. Here, they have pressing choices to make and the surreality that surfaced in the first novel deepens around them.

“This is a novel about pinball,” the narrator states. He’s not lying, and yet this simple plot leads to a surprisingly fulfilling and moving outcome. By the end of his search for the “three-flipper Spaceship” pinball machine he used to play in an arcade, pinball machines have been invested with an unexpected emotional resonance — an almost mystical significance that defies logic.

There’s a symmetry to the novels, and they work well when presented together. They both begin with the telling of stories and end with departures.

In these early forays, Murakami’s work already displays the wonder, melancholy and unreality that are his hallmarks. His is a world of inexplicable cats and disappearing lovers. “Wind/Pinball” shows us Murakami’s world and that the seemingly mundane can be truly magical and captivating.