By Michael Battista

Sports Editor

On Tuesday, Sept. 22, the world lost a true American icon. Not just a baseball legend, not just a World War II hero and not just the coiner of many iconic phrases, but a hero to people of all ages in all walks of life.

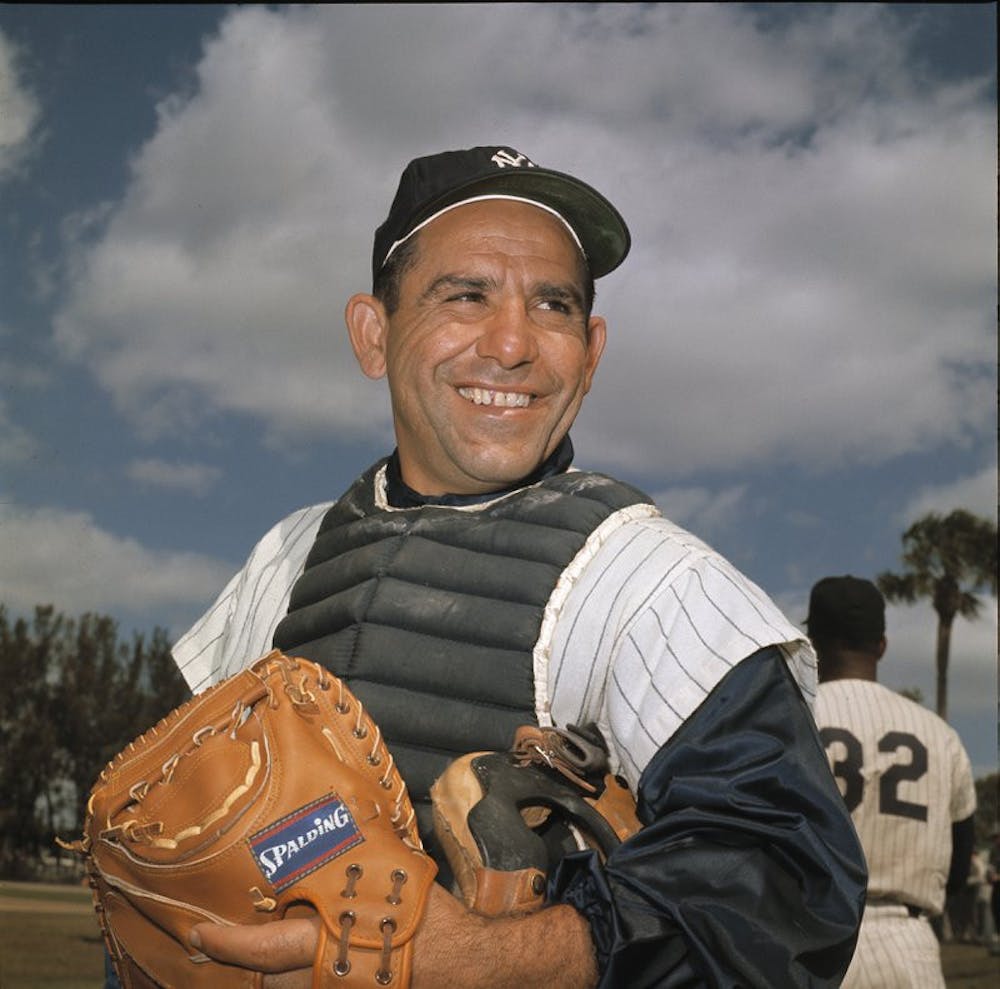

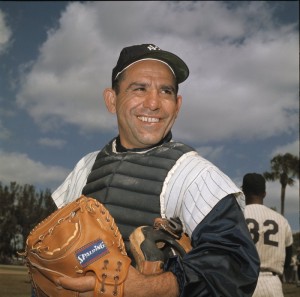

Lawrence Peter “Yogi” Berra passed away at the age of 90, leaving the world in silence after years of making us all laugh and smile. He was a 13-time World Series Champion (10 as a player and three more times as a coach), 18-time All-Star, three-time American League MVP, a member of the Baseball Hall of Fame and the Major League Baseball All-Century Team.

In 1942, the New York Yankees signed Berra and sent him to the minors. However, with the U.S. going to war, he had to drop his bat in favor of a rifle. Berra served as a Navy gunner’s mate during the D-Day invasion of Normandy. He was one of a six-man crew on a rocket boat, firing on German defenses at Omaha Beach.

After that, Berra’s career in Major League Baseball actually began in 1946. He excelled at hitting “bad” pitches, the ones most batters would either foul off or leave alone hoping they would be called balls. This, in turn, made him a master at bat control, allowing him to take low pitches deep with a “golf club swing” and driving high pitches down the line.

His work at the plate made him an essential piece of a feared Yankee championship dynasty. In 1947, the Yankees beat their crosstown rival Brooklyn Dodgers in seven games to capture the championship, and between 1949 and 1953, they captured five more in a row. Today, these teams are considered some of the best in the game’s history.

The next time the Yankees reached the World Series was in 1956, and it would be one of Berra’s iconic moments. During Game Five, Yankees’ pitcher Don Larsen pitched the only perfect game (to date) in World Series history. As the 27th batter struck out, in one of the most recognizable images of his career, Berra ran out and jumped into Larsen’s arms.

The image is unforgettable — both men in a moment, frozen in time. Before all their teammates rushed them, there was Yogi and Larsen together, a pitcher and his catcher.

After a few more seasons of play, and a few more rings, Berra moved his talents from the field to the bench. He worked as both a manager and coach for both New York baseball teams — the Yankees and the newly created New York Metropolitans (Mets). His tenure as a coach finished in Houston with the Astros in 1989.

Berra’s work off the field was just as important as his work on it. In 1998, the Yogi Berra Museum and Learning Center opened on the campus of Montclair State University in Montclair, N.J., The site, which houses memorabilia from Berra’s career, was created in hopes of teaching children valuable lessons such as to “preserve and promote the values of respect, sportsmanship, social justice,” according to the museum’s website.

Beyond that, Berra had a way with his words that made people laugh and scratch their head all within five minutes.

For example, he said “It ain’t over, till it’s over,” when talking about his Mets being in last place during the 1973 season, where they battled back to make the World Series. When asked how to get to his house, his directions were simple: “When you get to a fork in the road, take it.” When describing how the shade affects Yankee Stadium as he played, he said “It gets late early out there.”

I could fill this story with dozens of these “Yogisms” and still not be halfway done. My family actually had a direct encounter with this type of wit. A few years ago, my late great uncle and my brother went to an event to see Yogi Berra and get an autograph. My uncle had been at Berra’s first game, where he hit a home run during his second at bat. When he told Yogi this, he only looked at him and said “I was at that game, too.”

Berra’s work both on and off the field has made him an icon in the hearts of many. There’s a lot more I can talk about, but there isn’t enough space on this entire page to fit it all.

Yogi Berra was an unforgettable personality that left a mark on us all, no matter the age or team bias.

The 1993 baseball film “The Sandlot” says it perfectly:

“There’s heroes and there’s legends. Heroes get remembered but legends never die.”