By Mackenzie Cutruzzula

Review Editor

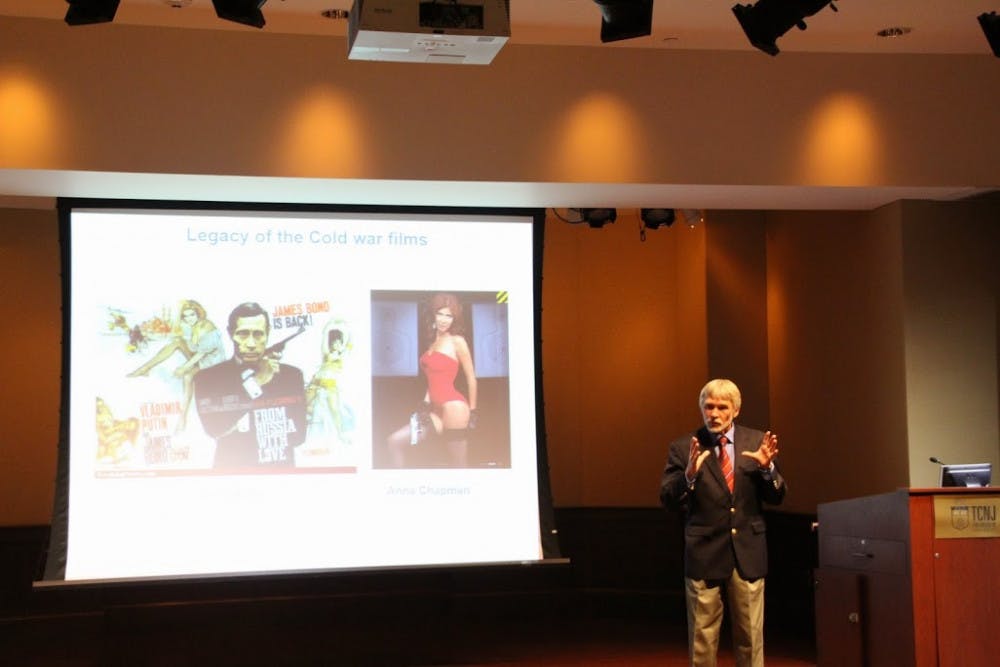

Fulbright Scholar Oleg V. Riabov visited the College on Tuesday, Feb. 3, to discuss his research on how Cold War propaganda reflected the cultural construct of enemies. Riabov is a professor in the Philosophy Department and director of the Center for Ethnic and Nationalism Studies at Ivanovo State University in Russia.

Riabov raised the question, “How did Soviet cinema represent the American gender order?”

To answer his question, he studied gender discourse as a set of representations of femininities, masculinities, sexualities, love and gender order in general. Through this study, he found that both America and the Soviet Union crafted the idea of what were proper masculine and feminine qualities based on their own countries’ set of values and beliefs and portrayed the enemy as having the opposite values.

Riabov stressed that gender identity was exploited in political mobilization during the Cold War because the threat of war of weapons emphasized that masculinity was represented by heroism and strength. To convince men to go to war, they had to believe that being a man meant he had to be a defender of the women and children. He presented a war recruitment poster used during World War I that featured a woman in distress in front of a war scene, asking the man before her, “Will you go or must I?” During the Cold War era, there were no battle to be fought, so the idea of gender and the way it was presented in propaganda had to change.

The Soviet Union used cinema to promote their propaganda between 1946 and 1955. More than 150 propaganda films were produced between both sides during the Cold War. In their film portrayals of Americans, they put major emphasis on men lacking the “normal,” masculine traits while females had an excess of the “normal,” feminine traits prominent in Soviet culture. More specifically, Riabov said that American women were seen as materialistic and vain compared to the hardworking, simple Soviet woman. The women of America were shown as victims of capitalism so that Soviet women would not be swayed by the “high life” of America that could be appealing. To continue to dissuade the Soviet women, films showed American women as rape victims, prostitutes and too willing to do anything to get to the top.

Riabov explained the paradigm between the two cultures representations using the Soviet propaganda film, “The Russian Question.” The film centered on a newspaper reporter in New York City in 1946 who wrote a positive review of Russia only to be blacklisted by the newspaper industry. His wife leaves him because he loses his job and can no longer afford the materialistic valuables she desires.

“The propaganda stressed that American men couldn’t be honest to become successful,” Riabov said. “Women couldn’t face a life of poverty because, according to the Russians, they were unable to love due to their hunger for money.”

The films were also used to promote the political systems of the home country through the idea of love and gender. The American film “Ninotchka” starring Greta Garbo tells the story of a rigid and stern Soviet woman who, after falling in love with a Parisian man, sees how the Western way of life is more suitable for her.

Riabov raised the point that having a Soviet female fall in love with a Western man was a tool to promote American masculinity as superior. He also reminded the crowd that the Soviets, of course, did the same for American women falling in love with Soviet men in their films.

The two opposing countries represented the gender order of the “main enemy” as contrary to its own and unnatural to its political systems.

“Riabov brought up a lot about Russian propaganda that I had never learned before,” junior finance major Rachel Benin said. “It was interesting to learn about another country’s propaganda.”

Riabov continues his Fulbright research at the University of Vermont, studying the history of symbols and ideas that have shaped the ideals of “Mother Russia.”