This article was written in response to Vincent Aldazzabal’s opinion piece “Capitalism 2013: Dow and Dirty,” published on April 3.

By Greg Burr

President of TCNJ Student Liberty Front

I’d like to thank Mr. Aldazzabal for responding to my piece, but he fails to address my position. Aldazzabal claims that I asked “where is the convincing evidence of harm from markets?” But, I never asked that question. I cherish this type of dialogue, but if we wish for this discussion to be valuable, it is vital that we engage each other’s actual claims and not make up questions.

Aldazzabal has confused market processes and political processes and in turn wrongfully blames markets for political decisions. Instead, American foreign and domestic policy is the result of a political process, the antithesis of the market process.

Aldazzabal says: “While Mr. Burr makes a most subjective argument that free markets are the best we have to offer, it operates under the false pretense that they are innately superior — a static representation — and never succumbing to the negative influences of “Big Brother,” socialism and communism.”

This sentence is gibberish. It seems that Aldazzabal is claiming that the problem is not a minimal state and markets, but that somehow markets lead to “Big Brother” (a large state) and socialism or communism (non-market economies). If the negative influences come from “Big Brother,” socialism and communism, then I invite Aldazzabal to join me in opposing socialism and communism and advocating a minimal state and free markets.

Indeed, the empirical record is clear: free markets have been far and away the best method of allocating resources, except in a relatively narrow set of cases in which voluntary transactions between two parties affect a third party. When possible, it is usually more efficient to internalize the externality through private means rather than through government action. In some cases, it may be necessary for government to safeguard the interests of third parties by instituting a regulatory mechanism that internalizes the externality. In those instances, it is important that the market imperfection be compared with government imperfection to avoid greater harm through government action.

The crash in 2008 was not “spurred on by deliberate misinformation distributed by those in power” but by an asset bubble in housing and a banking system that made risky investments because of government guarantees. Asset bubbles are psychological phenomenon in which actors have continual self-reinforcing expectations of higher prices. Experimental economists like Nobel Prize winner Vernon Smith have created bubbles in a lab setting, and they have shown that bubbles develop because of imperfect information not some conspiracy of misinformation by the mysterious “those in power.”

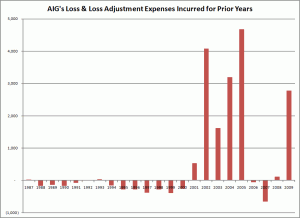

Bailing out rich AIG executives was not a market act but an act of government. If we truly had a “free market,” AIG executives in 2008 would have been in the unemployment line instead of flying around in private planes paid for with taxpayer dollars. Meanwhile, AIG would have gone through a controlled bankruptcy. It is utterly absurd to claim government bailing out AIG is somehow a market process. It was political action of the worst possible kind.

Mr. Aldazzabal again mistakes government and market processes in his analysis of the U.S. military, the CIA and Blackwater. The U.S. military is an arm of the state, not markets. The actions of the military are not directed by market price signals determined by supply and demand but by politicians. Likewise, Blackwater is under the employment of the U.S. government and is not acting in a market process. Market signals would have been far superior at protecting priceless artifacts than politicians. Actors in markets respond to price signals, and it is harder to think of a stronger signal than an item being valued so highly it is deemed “priceless.”

Throughout history, culture and art have consistently thrived in precisely those places where commerce has thrived. This is true of the Italian city states during the Renaissance, in the Netherlands during the 17th century and in London and New York City today. The decision to place a higher value on oil than on precious artifacts was a political decision, not a market decision, and these sorts of political decisions are the norm in both countries with market economies and those with non-market economies.

The crimes of governments, whether those with private economies like in the West or state communist economies such as the former Soviet Union, cannot be attributed to the market process. The problem is not that markets are tainting democracy, but that political power is in and of itself the problem.

Those countries that rid themselves of markets were not left with unspoiled politics, but on the contrary they were often left with far worse political systems than their counterparts with market economies. This was due to the increased state power that comes as a result of state economic control. The historical record is clear: the market economies of the world have brought their citizens to the most prosperous position in human history while the non-market economies have often left their subjects in squalor.