By Mark Marsella

Correspondent

The day the freshman was dreading had finally arrived — the day she was to receive the grade of her freshman seminar paper. English and secondary education double major Blaire Deziel wrung her hands nervously and squirmed in her seat as she asked herself: “Why did I leave this paper until the last minute? Why didn’t I do enough research? What am I going to do about this awful grade?”

After receiving her paper, she searched for the “C” or “D” she thought would be scribbled on the back page. She did a double take, however, when she saw the letter grade. Now she asked herself a different question: “How in the world did this paper earn a ‘B’?”

This was not the first time at the College that Deziel had asked herself this question.

“The grading standards of my teachers at college are definitely easier than those of my high school teachers,” she said. “College is a lot easier than I expected, for sure.”

According to many freshmen at the College, their high school teachers prepared them to expect much more work in college than they have actually encountered. It’s not just at the College that students are making these claims. There has been an increasing amount of national research supporting this claim — research suggesting that as time goes on, college grade point averages are climbing steadily higher for work that would have previously received lower grades.

“I have heard of grade inflation and believe it is an issue,” Peter Ulrich, a guidance counselor at Bergen Catholic High School in Oradell, said in an email. Ulrich, who guides hundreds of junior and senior high school students through the college process, said he believes “most college instructors grade fairly and students get the grades they deserve — for the most part.”

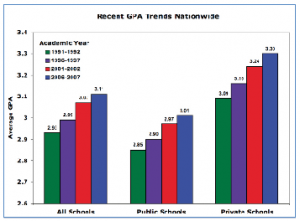

The term “grade inflation” was coined in a 2003 Washington Post article by former Duke University professor Stuart Rojstaczer, who has since compiled a wealth of data on the matter on his website, gradeinflation.com. The site shows thataverage GPAs have steadily risen over time at 231 schools in the U.S., at an average rate of .15 points every decade since the 1960s. The average GPA of over 60 of the country’s top colleges and universities has risen from 2.93 in 1992 to 3.11 in 2007.

“If I sprinkle my classroom with the C’s some students deserve, my class will suffer from declining enrollments in future years,” Rojstaczer wrote in his Post article. “In the marketplace mentality of higher education, low enrollments are taken as a sign of poor-quality instruction. I don’t have any interest in being known as a failure.”

The College’s GPA records seem to follow this trend as well. According to its online index of reports and grades, the school’s average fall semester GPA has risen steadily from a 3.13 in 2001 to a 3.22 in 2007.

While some may argue this rise is simply an indication of an ever-improving College, other popular N.J. public and private schools follow this trend as well.

Rutgers University has risen from a 2.60 in 1968 to 3.01 in 2006, Monmouth University from a 2.91 in 2005 to 3.03 in 2007 and Princeton University from a 2.83 in 1969 to a 3.38 in 2001.

Freshman history major Bill Toth believed he was experiencing grade inflation in one of his liberal learning classes last semester.

“You couldn’t fail a test,” Toth said. “(The professor)gives you a grade, and then he’ll curve it to a passing grade if you fail ... I got an 84 on my midterm and he gave me six extra points. He then decided to give everybody three points because ‘one of the questions was worded funny.’”

Some colleges have actually acknowledged the existence of grade inflation, and have taken steps to combat this trend. Princeton University, for example, publicly announced in 2004 that it would take steps against grade inflation by tightening its grading policy, and its average GPA has since decreased. In the 2008-2009 school year, “A” grades made up 39.7 percent of Princeton’s undergraduate grades, compared to nearly 50 percent in 2002-2003.

“I am aware of the phenomenon and that some institutions like Princeton have studied it more systematically than we (at the College) have,” said Stuart Koch, associate professor of political science, in an email.

When asked whether or not he saw grade inflation at the College, Koch said, “I think it is spread unevenly throughout the College with some faculty, departments and schools more prone than others.”

Koch also said he believes that some professors may give higher grades than students deserve to keep their reputations as competent teachers, “but probably more so to make life easier,” he said. “In our department, being seen as an easy grader would tend to hurt one’s professional reputation.”

Richard Kamber, professor of philosophy, has studied the phenomenon of grade inflation and has written or co-authored several articles on the subject. In an email, he said, “(Grade inflation) is a genuine phenomenon and it is national in scope. Yes, there has been grade inflation at the College for many years, though I stopped tracking it several years ago.”

Kamber also said that smarter incoming students are probably not the primary cause of grade inflation.

“There was a period in the college’s history when the rising academic caliber of admitted students may have been a key factor in grade inflation, but that was a long time ago,” he said.

Not everyone, however, believes grade inflation is a something to worry about, as other factors may be contributing to the steady rise in GPA.

“I think with the use of technology, the quality and scope of assigned papers and projects have improved over time,” Ulrich said. “Students can get more done in shorter hours if they work efficiently. However, I do not think that necessarily makes college life much easier.”

The idea of grade inflation itself is also challenged by skeptical students.

“I don’t think higher GPAs means grading should get tougher,” said Brian Perez, freshman health and exercise science major. “And I’m not saying that because I want easy A’s. I mean, I’m not afraid of a challenge. I just think that plenty of other unnoticed factors could be making GPAs higher — improved study habits, better education in high schools, higher college attendance rates.”

Conversely, Koch sees stricter grading as a possible combatant of grade inflation.

“The College has not figured how to handle grade distribution as part of the promotion process,” he said. “They are not presented. I think they should be monitored as part of personnel reviews, to help insure that instructors have reasonably strict standards.”

Some opponents of combating grade inflation argue that stricter policies force professors to feel pressured to grade unfairly. Sophomore accounting major Jack Murray feels that this mentality caused one of his professors to unjustly lower his class’s grades.

“He refuses to give us grades we deserve just for the sake of keeping his class average slightly lower,” Murray said. “He also doesn’t believe in a homework assignment or paper that deserves 100 percent. A paper I can somewhat understand, but if I complete a 10-point question-and-answer homework correctly, I think I should get full credit for it.”

Despite the arguments about how to handle grade inflation, the fact remains that grades have noticeably risen over the years when looking at online College grade records. But whether or not it really is a problem is something up for debate.

“Grade inflation especially hurts very good students,” Koch said.

For now, however, Deziel doesn’t see any imminent problem in grade inflation.

“It’s encouraging for me when I get a good grade. It motivates me to keep doing just as well next time. Of course, the higher GPA doesn’t hurt either,” she said. “As long as I learn what I have to learn, I’ll deal with whatever cockamamie grade my professor wants to throw at me.”